Hidilyn Diaz

to Olympic glory

ZAMBOANGA CITY, Philippines – On August 8 at 3 a.m., Emelita Diaz knelt in front of a mini altar in their mint green bungalow in Barangay Mampang, Zamboanga City, holding her rosary and praying ardently to God to guide and bless her favorite daughter who was 11,000 miles away in the Brazilian city of Rio de Janeiro competing in the Olympics.

Unlike millions of Filipinos across the globe who were closely watching and rooting for weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz in her third consecutive appearance on the Olympic stage, 53-year-old Nanay Emelita could not watch her daughter compete since the Diaz family's old television set could not get a clear signal that would allow them to watch the live telecast.

So they just prayed to God for Hidilyn's success.

And while she may be a 25-hour flight away from Rio, Nanay Emelita could feel the weight that was on the shoulders of her daughter who at that moment was squatting down in the middle of the Olympic stage, undisturbed by the millions of eyes watching her.

The 25-year-old Mindanaoan lifter held the 112-kg barbell, then faced the audience with a feisty look while biting her lower lip.

It took her five seconds to gather enough strength to carry the crucial second clean and jerk attempt before she had the entire barbell, which weighed more than two sacks of rice, on her shoulders.

A couple of seconds later, Hidilyn raised it above her outstretched arms, with steady hands and her head down. 1, 2, 3. She did it!

Hidilyn was assured of a bronze medal in the Olympic Games, the first for the Philippines since 1996 when boxer Mansueto "Onyok" Velasco settled for silver in a controversial gold medal match in the Atlanta Games.

The 5-foot-2 female athlete put the barbell down then waved her right hand to the appreciative crowd of Rio de Janeiro with a grin on her face, knowing she will be bringing home a medal that was 20 years in the making.

She threw her fists up on the air as she went down on the Olympic stage amid applause in appreciation for the relatively petite Pinay's accomplishment.

"Lord, thank you," Diaz shouted as she returned backstage.

Diaz, who would lift a total of 200kg, almost four times of her weight, eventually claimed the Olympic silver medal in the 53kg of the women's division -- a feat that no other Filipina athlete has done before.

The historic triumph of Hidilyn was celebrated not just by Filipino sports enthusiasts but by entire Pinoy communities in the world. The lifter's team, comprised of big men, couldn't hold their tears back, aware that they have done what seems to be impossible for the lean 13-man Philippine contingent in Brazil.

Nanay Emelita, however, remained clueless that her prayers have already been answered. She was on the third joyful mystery when her nephew, Allen Jayfruz Diaz, knocked on their door, shouting for joy, as he told the extended Diaz clan of Hidilyn's win.

In the 700-hectare village of Barangay Mampang in Zamboanga City, everyone was awakened by the good start and started to gather in the makeshift gym of Hidilyn in front of their house.

Mommy Emelita continued praying. However, she was soon distracted and her heart was beating fast again as her neighbors continued their jubilation.

FROM GROUND ZERO TO THE HOME OF A SPORTS HERO

Hidilyn's hometown of Mampang is a mangrove-surrounded barangay more than 10 kilometers away from the pueblo – the term used by the Chavacano-speaking locals to refer to the town proper.

Despite some developments in the barangay, many Mampangueñoes still live barely above the poverty line.

According to a barangay councilor, most residents of Mampang are still without running water and have to fetch water hundreds of meters away every day for taking baths, washing clothes and even for drinking.

Hidilyn used to fetch water when she was still a young girl – which could help explain her strength. She carried pails of water from a rationing station in the boundary of Mampang and a neighboring barangay – more than 300 meters from their house.

This traditional quiet village where farming remains its primary source of income made headlines when it became ground zero during the Zamboanga siege in 2013.

Three years after the armed conflict between the military and a faction of the Moro National Liberation Front that claimed hundreds of lives, Mampang returned to the spotlight but this time with a far happier ending. In a village where weightlifting is the favorite sport, Mampang and the rest of Zamboanga City will now be remembered as the hometown of an Olympian.

Days after Hidilyn's Olympic win, she returned to Zamboanga to a hero's welcome. Accompanying her from the airport in Manila were her parents Nanay Emelita and Tatay Eduardo who quietly stayed by her side as hundreds of their kababayans greeted their arrival.

POVERTY AND PERSEVERANCE

Emelita, to whom Hidilyn dedicated her silver medal, admitted that she was worried at first when she allowed her daughter to train for weightlifting. She was unsure if the sport fit the studious young girl -- the fifth in a brood of six.

Before Hidilyn started winning in weightlifting tournaments, the Diaz residence was just a tiny makeshift house. Back then, they used to dine outside because the house was too small to accommodate the family of eight during mealtime.

Growing up with limited resources, Hidilyn had no choice but to help her father till their land under the heat of the sun. But this didn't prevent her from finishing her studies.

"Si Hidilyn ay mabait na bata, masunurin nung bata, masipag sa pag-aaral. Kahit tres pesos lang 'yung baon niya, eh pumupunta talaga siya sa paaralan para mag-aral dahil gusto niya talaga makatapos sa pagaaral," Emelita said in Chavacano, Zamboanga City's local dialect.

Living in a compound with almost all her relatives, Hidilyn spent her childhood with her cousins, who were there to witness how her career in the sport bloomed through the years.

Among them is Allen Jayfruz Diaz, now 31, who was instructing aspiring lifters -- mostly their relatives -- in the bamboo-woven paneled gym in front of the Diaz house, where Hidilyn held a jampacked press conference just a day earlier.

As he placed rubber mats on the semi-cemented floor of the 15-square-meter gym that trains young dreamers who make do with a limited number of bars and deformed and improvised plates, Zamboanga's regional weightlifting coach recalled how he and Hidilyn built the gym five years ago.

Allen said it was 36-year-old Catalino Diaz Jr. who encouraged them to try weightlifting. Cata, as they fondly call him, gathered his young cousins, including Hidilyn, in the early 2000s to lift.

As a young girl, Hidilyn was called "morita" by her neighbors – a Chavacano term for a dirty-looking, black-skinned, untidy person. But what Cata saw in Hidilyn was a promising weightlifter.

SAMPALOC GYM

Cata had to convince Nanay Emelita to allow Hidilyn to train in another barangay, two rides away from the Diaz compound.

"Nung una ayaw ng nanay niya kasi babae. Halos lahat ng na-train ko puro lalaki tapos kaunti lang babae that time. Sabi ko, 'Hayaan mo na auntie, ite-train ko lang siya. Tapos kung may potential siya, may mararating siya one day,'" Cata, who is now a cross fit trainer in Davao City, told ABS-CBN News through phone.

"Nakita ko kasi sa body type niya, hindi talaga pang girly-girly. In-encourage ko talaga 'yung auntie ko na isali si Hidi sa weightlifting."

In the beginning, Cata and Allen brought Hidilyn to Bgy. Pasabolong to train under a sampaloc tree whose branches fanned out wide enough to give shelter to the young students of weightlifting.

The tree stood in the middle of a vacant lot near the national highway of Zamboanga City. As beginners, Hidilyn and her cousins used to lift wood cut from ipil-ipil trees as they could not afford to buy a set of barbells. Hidilyn also lifted cemented barbells before she finally got her hands on a real-steel barbell.

Ever since, Hidilyn showed much promise in weightlifting as she could lift heavier barbells than the young boys in her batch.

After two hours of training every day, aspiring lifters usually ate boiled cassava partnered with shrimp paste. According to residents in Pasobolong who witnessed how Hidilyn started, it was her favorite. Kids were satisfied with just cassava or rice with salt to fill their hungry stomachs.

The struggles of Hidilyn were not confined to training. Being raised in a poor family, she also had trouble commuting to the "Sampaloc gym." But nothing could hinder a determined young athlete.

Hidilyn didn't just carry pails of water; she also used to bring vegetables to sell at the "tiangge," as the primary source of income of their family. And when the land which her father used to till was sold, she shifted to selling fish.

But sometimes their profit was not enough for their family and she and her brothers had to make do with salt and soy sauce to flavor their dinner.

Hidilyn also ventured into car washing to help her parents and augment her daily allowance.

MOVING TO MANILA

Hidilyn could have tried other sports such as baseball, which was the prominent sport back then in Zamboanga City before it was overtaken by weightlifting; or basketball, given that she grew up in a family composed mostly of boys, but fortunately she took a different path.

She soon started winning local weightlifting competitions and got invited to join the national team. But the good news came with much sacrifice, as this meant moving from Zamboanga to the national weightlifting team headquarters in Manila.

With Hidilyn living miles away from their home, Nanay Emelita felt helpless when her daughter would call whenever she was not feeling well or just to share with her mother how tired she was after training.

Holding back her tears, Nanay Emelita remembered how she much wanted to help her daughter but had to be content with reminding her through phone to take her medicines and rest – the only thing a mother can offer to her child who was far away.

"Bilang isang ina, gusto ko ako ang mag-alaga sa anak ko. Natatakot ako na baka may mangyari sa kanya. Hindi ko kakayanin," a worried Emelita shared.

Hidilyn too longed for her mother during those trying times. Although determined to create a name for herself in the sport, she couldn’t deny that she was lonely as she trained in Manila, away from the arms of her mother.

"Sobrang hirap, walang nagla-love," the athlete recalled. "Alam mo 'yun 'pag pagod ka na wala kang kausap so tinatawagan mo nanay mo na lang sa malayo, Wala kang magawa kasi malayo ka nga."

Now Hidilyn and Nanay Emelita are trying to make up for the time they sacrificed for the silver medal that shines like a gold.

"Ang ginagawa ko kapag nandito si Hidi, binubuhos ko lahat. Bumabawi ako sa time na wala si Hidi lalo na yung pagluto ng mga paboritong ulam at pagkain ni Hidi. Gusto ko makabawi sa mga time na wala ang anak ko dito," she shared.

THREE OLYMPICS

In Mampang, no one ever doubted that one day she will be stepping on the podium of the Olympics.

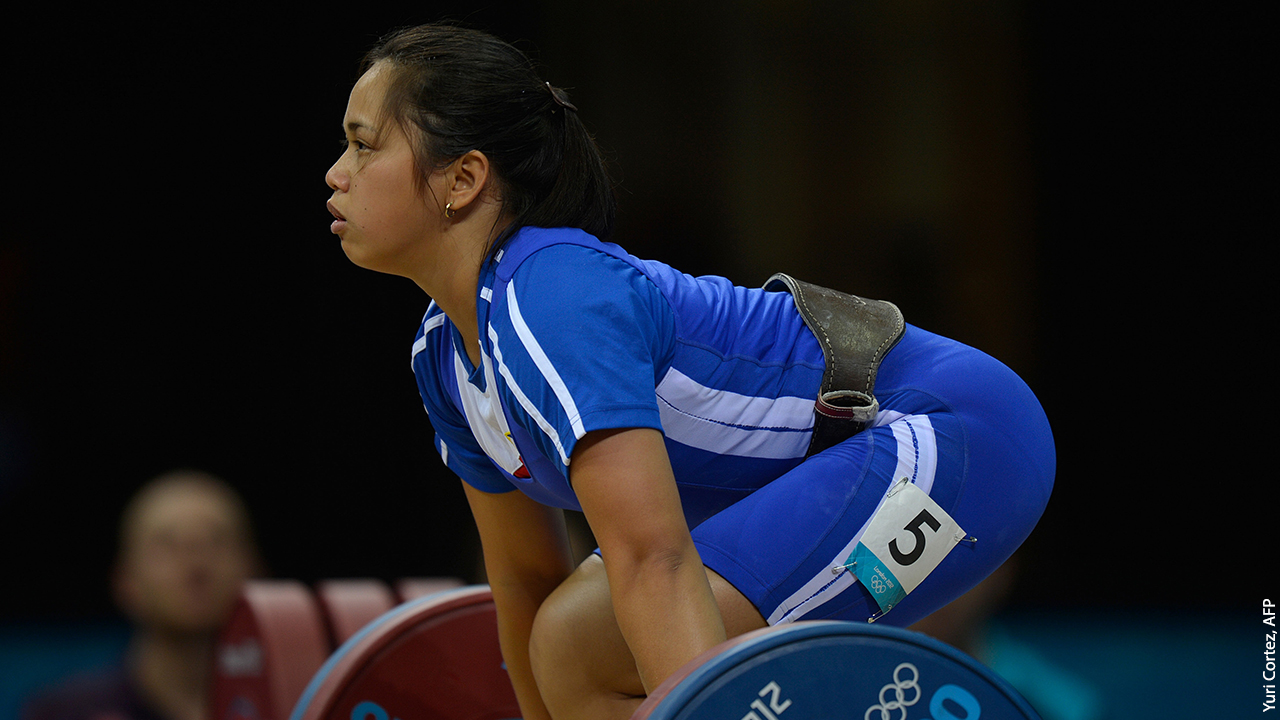

After a promising stint in her first Olympic stint in Beijing as a wildcard entrant, expectations were high coming into the London Games. She was even chosen as the flag bearer of the Philippine contingent. However, after recording a personal best lift in snatch, she crashed out of the competition in the clean and jerk off a failed lift.

The loss took a toll on her. A couple of years after the 2012 Olympics, the Pinay lifter suffered an injury which prohibited her from competing and training.

Setback after setback, Hidilyn found herself in yet another low point of life as if she was already at the twilight of her career. She started to lose focus and missed several important competitions abroad. Dropped from the Philippine lineup in most of the international games until 2014, she nonetheless picked herself up and found her way back on track.

Aware of what is at stake should she be permanently booted out of the national team, Hidilyn agreed to the demands laid out to her by Philippine Weightlifting Association Vice President and now city councilor Elbert Atilano which included stepping down to the 53kg division from 58kg. It was not easy for Hidilyn, who admitted that she has a big appetite, to cut her weight by five kilos.

But destiny must have intervened, yet again. Despite difficulty of maintaining her weight, she placed better in international fights and eventually secured her third successive Olympic ticket.

Hidilyn was tested one last time with yet another roadblock just two months before the Rio Games. After spending almost an entire year in Manila to focus on training, she returned to Mampang to visit her then bedridden granny almost too late. Her 93-year-old Lola Ema passed away after two days, as if she was just waiting for her granddaughter to arrive and see her.

GIVING BACK

While Manila trained Hidilyn in the sport, it was in Mampang where she first learned how to win in life.

Hidilyn promised to give back to her beloved hometown by purchasing the lot in front of their house and construct a well-built weightlifting gym.

But in the meantime, that makeshift gym she helped build in front her house midway through her career continues to serve as a grassroots venue for aspiring lifters in Mampang.

With a bunch of weightlifting students still left in the compound, Hidilyn is deeply interested in honing and molding the next batch of athletes who might give the Philippines its first-ever gold medal.

Among the standouts is Mary Flor Diaz, whose form and technique seemed quite advanced compared to the others who were practicing that day. With her height and good body built, the 17-year-old is currently part of the Philippine national team and began lifting barbells at the age of 8, three years younger than her cousin Hidilyn.

"Yung mga pinsan ko't kapatid ko puro mga weightlifter din po, kaya na-engganyo ako na subukan 'yung sports na ito," said Mary Flor, who has already collected bunch of accolades under her belt, including several gold medals from the annual Batang Pinoy competition.

Idolizing her older cousin, Mary Flor is fired up to reach greater heights given the support of Hidilyn herself.

Mary Flor is literally stepping into the shoes of her cousin -- the same pair Hidilyn wore in several international competitions, such as the Asian Games – and she hopes she will also inherit the same strength and success Hidi had with them.

Just as Hidilyn has expressed her intention to go for her fourth Olympic Games in Tokyo in 2020, Mary Flor is also gearing up for a qualifying competition in Japan which will be her first international exposure.

And as she puts on the lifting shoes her bemedalled cousin gave her, Mary Flor is hoping to continue the weightlifting legacy of their family and Mampang as the country's next Hidilyn Diaz.