Nakaya knows to adjust to the tides. He sets out to catch fish before dawn when the tide is low and makes up for sleep at noontime. But as a fisherman in Taliptip, the sea takes charge not only of his hours, but the rest of his family’s lives.

Nakaya, 57, has lived in Taliptip for almost 4 decades. He has witnessed roads repeatedly piled over with new layers of concrete as the government tried to keep streets above sea level during high tide.

“Apat na beses na, mula noong tumira ako noon dito. Hinahabol nila yung tubig, ‘pag tumaas ang tubig, pataas din sila ng kalsada,” Nakaya said.

(It has happened 4 times since I moved here. They chase the water; when its level rises, they also raise the road.)

To keep their home at the same level as the road in front, Nakaya's family spends up to P8,000 every time soil, gravel, and concrete are dumped and leveled onto their floor.

Pointing to the ceiling of his house, Nakaya said, "Dati hindi namin maabot ‘yan. Ngayon yumuyuko ka na, kasi tambak kami nang tambak, habol kami nang habol.”

(Before, we couldn't reach that. Now, we have to bend because we’ve piled on so many layers on the floor to keep up with the road's level.)

Crouched, Nakaya's head still brushes the ceiling. The fuse box, which should be out of children's reach, is now just around 3 feet from the ground.

Roque Nakaya’s home has had soil, gravel, and cement dumped and piled on several times to catch up to the road which the government keeps elevating as the tide keeps rising. Now, the tide is almost catching up to their home again.

This is life by the sea for residents along the 1.3-kilometer Bagumbayan Street in Barangay Taliptip. The road connects Bulakan to Obando town by bridge, and further south to Valenzuela, Malabon and Navotas. It provides a cheaper route to get to Metro Manila from Bulacan, instead of driving inland and through the expressway.

But with the seawater regularly encroaching on the road, residents have no choice but to adjust.

Bulakenyos came up with what is locally dubbed as “kolong-kolong”, also called “kuliglig” by visitors; a hybrid vehicle consisting of a motorcycle with its engine elevated some 3 to 4 feet above ground and a large sidecar attached.

Farmers typically use this type of sidecar to transport pigs for sale. But in Taliptip, it carries people and motorcycles.

Whenever the tide is too high for Nakaya to go out to sea, he drives his kolong-kolong to earn a few hundred pesos on what would have been time to catch up on sleep.

“Halos lahat ng dumadaan, ang daing, problema sa pagpasok. Imbis na ang pamasahe wala na dahil naka-motor [sila], yung pang-gasolina sana, ibinibayad po nila dito para makadaan at makapasok,” said Jay Fantanilla, a barangay tanod, who helps drivers like Nakaya load passengers and motorcycles onto their kolong-kolong.

(Everyone who passes by complains. Instead of being able to save on fare because they’ve invested in their own motorcycles, they now have to spend what would have been gas money to haul their motorcycles over and across the sea water.)

Each ride through the sea-submerged road costs passengers P150 to P200, depending on the size and weight of their motorcycle, or how many passengers will be loaded.

Some kolong-kolong ferry students whose face-to-face classes resumed this year. The children sit precariously on the sidecar’s metal frame and prop their feet on the opposite rails to keep their shoes dry while the kolong-kolong splashes through the road.

The unwitting drivers of larger vehicles who dare cross Bagumbayan during high tide almost always get stranded on the road with a soaked engine. Visitors unfamiliar with the narrow road risk falling off of its 2 lanes which are hardly visible under the 3 to 4-feet-tide.

Locals know well enough to avoid the road even when the tide eases as prolonged and repeated exposure to saltwater damages their vehicles' metalwork and costs them money to repair.

Bulakan, Bulacan is home to some 81,000 people, according to the Philippine Statistics Office's 2020 census. Some residents have built homes away from the main road, on land much lower than those near Bagumbayan Street.

There has always been water in front of Analyn De Jesus’s home, near one of the smaller rivers that cut across Bulakan and lead out to Manila Bay. Here, a fish pen serves as their family's front yard.

As the river's water level keeps rising, De Jesus and her neighbors have propped their homes on a combination of stilts and concrete to keep their floors dry. But when the rains are heavy and the tide is high, water seeps into their home and they wake up on a drenched bed and pillows.

“Sobrang hirap at perwisyo sa amin. Natutulog kami madaling-araw, gigising kami, nangangamba na ‘yung higaan namin basa na po. Nararanasan namin na magbaha, pero hindi na maglimas ng loob ng bahay, matulog nang maaga para abangan ang tubig, ‘di makatulog,” De Jesus said.

(It’s very difficult. We sleep late and wake up in the middle of the night worrying if the water has gotten to our bed. We are used to floods, but never this high. We try to sleep early so we could be awake when the water comes in, but it’s hard to fall asleep.)

There was a time when they could cross the fish pen with the water only lapping up to their thighs. Today, the water is over 5 feet high, and if they don’t walk carefully along old “pilapil” or embankments used to divide the pens, they would not be able to cross onto the paved elevated road.

De Jesus’ daughter and her neighbor’s children get on a flimsy tub boat twice a day to and from school and their home.

The boat sways as each passenger climbs on. Nobody moves as the bangkero in front pulls the boat forward by a rope tied to a tree beside the street. The thought that the boat might overturn and drown the children plagues De Jesus.

De Jesus and Nakaya both hold titles to the land on which their homes sit. Despite a life altered and made difficult by the sea, leaving the only property their families have is unthinkable.

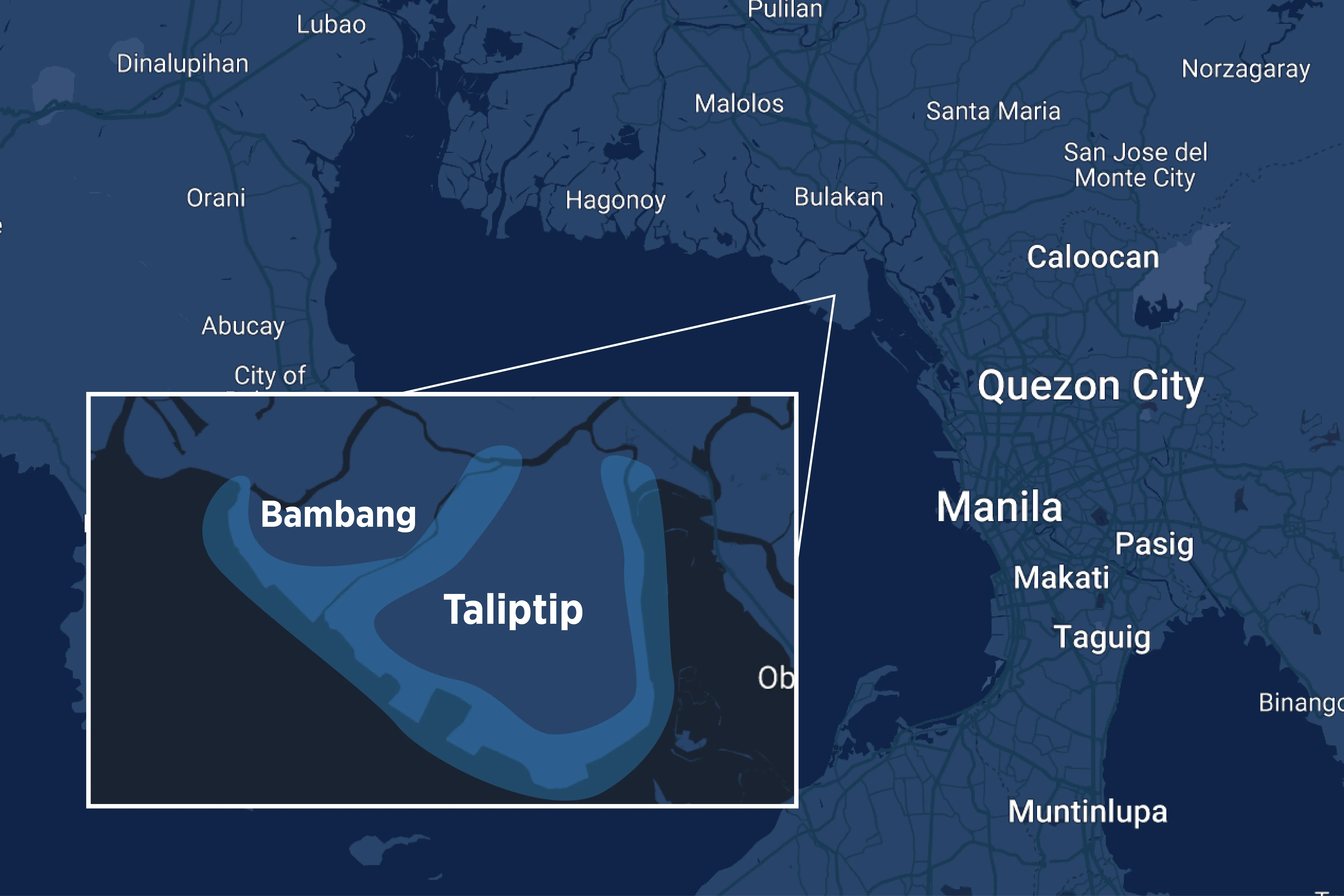

Taliptip is not the only neighborhood in the town of Bulakan where the tide has changed residents’ lives.

Barangay Perez lies further inland, sandwiched by Barangays Taliptip to its southeast and Bambang to its northwest. The arch that marks the boundary between Perez and Bambang is bordered by a small river and rice paddies.

During high tide, the river overflows onto the paddies and water submerges the road under the arch. But the area remains a main thoroughfare connecting the 3 villages, so local farmers and fisherfolk bring their harvest and catch there, lay them out on planks just high enough to clear the tide, and wait for passing buyers.

Residents wade through knee to thigh-deep floods to buy food in this makeshift talipapa over water. Payment and change is handed over carefully, lest it fall down and disappear in the current of the water from the river.

Along the road towards Bambang, some residents bring plastic chairs out on the pavement and pass the afternoon chatting with neighbors, soaking their feet in the cool seawater at their doorstep. They shout a warning to visiting motorists to refrain from driving onward when the tide is too high.

The homes on the northern side of Bagumbayan Street are flooded whenever the river overflows with the rising tide.

Levy Litao and her husband Mattias live in one of these houses. During high tide, knee-high floods enter their home which has also been elevated with layers of gravel and concrete several times since they first bought the property as a young married couple 53 years ago.

When the river overflows, Mattias’ bedroom is submerged. The rooms at the back of their house can no longer be occupied. Their dog barks from a bench, where it has perched itself as the water rose.

“Wala na kaming mga nakababang gamit, nakataas na lang. Mahirap, eh syempre magtitiis tayo. Umuurong naman 'pag hapon. Sa isang linggo, tataas ulit yan,” Levy shared.

(All our things are kept high. It’s difficult but we make do. The tide ebbs in the afternoon. But it comes back and it happens all over again the week after next.)

The tide that rules the lives of residents in Taliptip, Perez, and Bambang may be the first suspect behind the area's regular flooding. But this is not the only factor, says University of the Philippines Marine Science Institute professor Dr. Fernando Siringan.

Bulacan is part of a wide flatland north of Metro Manila, elevated only slightly above sea level. Close to sea and with vast mud deposits, the coastline used to be filled with mangroves, which have been replaced with fish pens.

A 2006 study by Siringan with geologist Dr. Kevin Rodolfo described the coastal plains as “so low and flat that the one-meter elevation extends 10–20 kilometers inland.”

“Thus, normal spring tides only 1.25 meters high extend many kilometers upstream, and even small rises in relative sea level translate into large inland encroachments,” the study said.

“The plains comprise almost 3,000 square kilometers, extending southward from Angeles City and Arayat town to the coast, which stretches from northeastern Bataan eastward and southward to KAMANAVA,” it added.

The coastal areas west of these plains are also naturally close to deltas where rivers empty water and sediment into the ocean.

“Kung sapat ang dami ng sediments na pumupunta doon, ang naiipon sa kanya ay pino [na klase ng lupa], hindi graba, hindi buhangin, kundi mostly, putik,” Siringan explained.

“At ang putik kapag pinagpatung-patong natin, several meters thick, ‘yung bigat ng putik mismo on top of another package ng putik ay magiging sanhi ng pagkapipi, pinipipi mo ‘yung nasa ilalim. Ang pagpipi nito through time ay siyang magiging sanhi ng paglubog ng lupa,” he continued.

(If enough sediments settle in these areas, the type of soil which piles up is very fine. It isn’t gravel or sand, it’s mostly mud. When you put layers of mud on top of each other several meters thick, the weight of the mud will press down on the layers below. Over time, this will cause land to sink.)

This compaction of soil is just one of the several factors contributing to the floods in Bulacan. There is also land subsidence.

Land subsidence occurs when large amounts of groundwater is drawn through wells for use above ground. Bulacan Environment and Natural Resources Office (BENRO) head Atty. Julius Degala admitted that the province relies heavily on groundwater extraction for its residents’ use.

“Sa totoo lang naman po, in the whole of Bulacan, talagang highly dependent tayo sa extracted water from the ground,” Degala said.

(To be honest, the whole of Bulacan province is highly dependent on extracted water from the ground.)

Siringan clarified, “Hindi masama na kumuha ng tubig sa ilalim ng lupa. Ang hindi maganda ay kung masyadong mabilis at masyadong madami ang kinukuha nating tubig sa ilalim.”

“Ito ay resource na meron tayo, pwede nating gamitin ito. Ang nangyayari lang, ang paggamit natin ay mas mabilis kaysa doon sa natural rate ng pagpapalit ng tubig sa ilalim, kaya parang nauubusan ng tubig sa ilalim,” he said.

(Extracting water from the ground is not bad. It is a resource we have which we can use. What isn’t good is when we extract too much and too quickly, faster than the natural rate for the water underneath to replenish. So the groundwater runs out.)

Groundwater in aquifers, or bodies of rock that allow water to move easily, exerts pressure on the mud below and on top of it, keeping these layers apart. When groundwater is extracted and sucked out of these aquifers, that pressure is lost.

“Kung ang magiging pressure doon sa loob na pinagkukunan natin ng tubig ay magiging negative, it will force yung pag-release ng tubig ng clay layers. ‘Pag nag-release sila ng tubig, sila ay iimpis, at ‘yung kanilang pag-impis ay siyang magiging sanhi ng paglubog ng lupa,” Siringan continued.

(When that outward pressure becomes negative, it will force the release of water in clay layers. When the water is released, the layers deflate, and as they do, the land above sinks.)

In Manila, the land sank between 5 and 9 centimeters annually from 1991 to 2003, while the Pampanga delta's land subsidence was at 3 to 9 centimeters per year, according to Siringan and Rodolfo’s study.

Land subsidence has not stopped. From 2015 to 2020, Manila experienced land subsidence at 2 centimeters per year according to a study published last March in the Geophysical Research Letters from the Graduate School of Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island.

Rising sea levels also figure into the equation.

“Ang Pilipinas ay isa sa mga nakararanas ng pinakamabilis na pagtaas ng dagat,” Siringan said.

(The Philippines is one of the countries with the fastest rates of sea level rise.)

The country's seas are rising 3 times faster than the global average, PAGASA climate change data chief Rosalina De Guzman said earlier this year, citing a joint study with the United Kingdom's Hadley Centre.

This has a huge impact on the country's coastlines, as 70 percent of the Philippines' municipalities are located in coastal areas, De Guzman noted.

With factors on land and in the sea closing in on coastal communities such as the neighborhoods of Taliptip, Perez, and Bambang, locals can only adjust. Immediate options include those already being done: raising the level of homes and learning to live with the tide.

But these solutions can only last for so long: sea levels will only continue to rise. Repeated renovations to elevate roads would cost the government huge sums, said Siringan.

“Expected na ang nararanasan ngayon ng mga tao sa coastal communities, kung walang intervention ay lalala lang. Hindi rin kaya ng local at national government na ganun ang approach kasi ang daming communities, buti kung 1 o 2 lang, kaso ang dami,” Siringan said.

(It can be expected that what people in coastal communities experience will only get worse without intervention. It will not be sustainable for local governments to keep adding layers onto roads because there are so many communities. It might be doable if there were only 1 or 2, but there are too many.)

Bulacan Governor Daniel Fernando agrees.

“That is not the solution, sayang ang pera ng gobyerno, let us save our money at pag-isipang mabuti kung saan ilalagay: mag-dredge talaga. Dapat magkaroon ng simultaneous dredging sa lahat,” Fernando said.

(We’ll only be wasting money. Let us save that money and think about where to put it. The solution is dredging. There should be simultaneous dredging everywhere.)

Dredging refers to the removal of sediment and debris from the bottom of rivers and other bodies of water. To address widespread and frequent flooding, the Bulacan government turns to dredging, a solution tapped by other cities with riverside residential areas like Pasig and Marikina.

“Sa ngayon ang ginagawa namin na temporary solution ay ang dredging,” Fernando said. “Ngayon magkakaroon kami ng intensified na pagde-dredge, kaya nagdagdag ako ng mga daraga, this year, magpo-procure ako ng 4 pa na daraga... at inumpisahan natin ito sa District 1 (Malolos, Bulakan, Calumpit, Hagonoy, Paombong, Pulilan).”

(Dredging is a temporary solution. We are intensifying dredging efforts, I procured more equipment to do this, and we have already begun in District 1.)

Fernando sought the help of San Miguel Corp. (SMC) president Ramon Ang in this undertaking. SMC is building the New Manila International Airport along the coast of Bulakan, Bulacan and it is expected to start commercial operations by 2027.

“We talked to Ramon Ang, at noon pa man ay ipinangako na sa atin yan, na talagang tutulong siya sa pag-control sa pagbaha. ‘Yun naman ang ipinangako niya, bago pa man ma-create ang airport. Sinabi niya sa akin na sa kaniya ang major rivers, at sa amin ang local rivers. Nag-agree kami, verbally,” Fernando said.

(He promised to us even before the airport came along that he will help control flooding in Bulacan. He committed to attend to major rivers, so the local government can work on local rivers. We agreed to it, verbally.)

Ang has started dredging operations in Tugatog, Malabon, said the governor.

Other flood mitigation measures that the provincial government eyes include the construction of multi-purpose seawalls that also function as roads and dikes, as well as the cleanup of rivers and waterways.

While Siringan’s recommendations align with the provincial government’s plans to clear waterways, he said the dredging of rivers could be reconsidered.

“Meron namang tulong ang dredging. I-define natin: ang karamihan ng mga dredging projects ay pagpapalalim lamang ng kanal, at ang ginagawa lamang nito ay pabibilisin niya ang daloy ng tubig sa panahon na maraming lumalabas na tubig, tulad ng tag-ulan," said the expert.

“I-dredge ko siya, pinalalim ko siya, pero hindi ko naman in-address ‘yung pagbaba ng maraming sediment. Dumating ang isang baha, ikalawang baha, ‘yung dinredge ko na ginastusan ko nang malaki ay mawawala na rin, kasi ang daming sediments na bumababa, at natabunan ulit ‘yung nilaliman kong bahagi. Oo, nakatulong ang dredging in addressing flooding, pero ito ay short-lived.”

(Dredging does help. But let us define dredging: most dredging projects only deepen canals, and what this does is allow water to flow faster when there are large amounts of it, like during the monsoon season. You dredge waterways, you make them deeper, but you do not address the amount of sediment that flows down. When a flood or two come, these waterways will become shallow again, wasting the amount of money spent on dredging projects. Dredging helps address flooding, but it is short-lived.)

Siringan recommended restoring the previously uninhabited spaces near rivers and waterways, and if possible, even make them wider to give water enough space to make its way back into the ocean.

“Ang natural setting noong wala pa ang mga struktura na humaharang sa daloy ng tubig, ‘pag tagbaha, tataas ang tubig. Pero ‘yung kaniyang pagtaas, since pwede siyang kumalat sa malawak na lugar, ‘yung pagbaha ay hindi ganun kataas. Tinatawag natin silang floodplains, at iyon ay natural features. Ang kaso, ang floodplains na ‘yun in-occupy ng tao. So saan ngayon pupunta ang tubig?” Siringan explained.

(The natural setting of floodplains when structures did not obstruct waterways is that during flooding, the water rises but it could spread over a wide area. The flooding is not that high. We call them floodplains, and these are their natural features. But now that floodplains are occupied by people, where can the water flow?)

BENRO agreed and said removing obstructions from waterways was ongoing. But the provincial government reported limitations to compliance.

“Inuuna po natin ang hazardous at risky areas, pinakikiusapan na natin ang informal settlers na hindi sila pwede doon. Kailangan ng tulong ng barangay. Kailangan bantayan nila ang nagtatayo sa gawi ng daluyang tubig, bawal na po iyan,” BENRO head Atty. Degala said.

(We are prioritizing clearing hazardous and risky areas. We tell informal settlers they are no longer allowed there, but we need the help of barangay officials. They have to keep an eye on these areas to keep people from building structures and settling there.)

“Matitigas lamang talaga ang ulo, bumabalik ulit. May pabahay nang ginawa ang NHA ‘di ba? Pero ‘pag binibigyan sila, ang nangyayari, bumabalik,” Fernando added.

(But they are stubborn. The National Housing Authority has already offered housing and relocation. But the residents keep returning.)

As for the effect of groundwater extraction on sinking villages, the Bulacan government said it was considering sourcing water externally and looking into desalination and maximizing rainwater collection.

In August, the Bulacan provincial government held a dialogue on proposed flood solutions with representatives from the Economic Affairs Section of the Netherlands Embassy. The Netherlands funded the North Manila Bay Flood Protection strategy, a “small follow up project after the Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan (MBSDMP) and was finalized last April 2022."

“Ginagawa po namin ang aming tungkulin sa abot ng aming makakaya most especially sa flooding. Sino ba naman ang may gusto na magbaha? Pati ang likod-bahay namin, binabaha, noong araw naman, maliit pa ako hindi naman ganoon ‘yun, pero ngayon ganoon,” the governor shared.

(We’re doing the best we can, most especially on flooding. Who wants to be flooded anyway? Even my own home gets flooded. When I was younger we never experienced it but we do now.)

But can the government implement its temporary interventions and plans fast enough?

Seawater has already seeped into communities further north, in the rice fields beside Bagumbayan road.

Here, Rochelle Buhay’s home stands on stilts on what used to be rice fields in Barangay Bambang which are now waterlogged with sea water. It has been a year since she was last able to harvest rice from the field beside her home.

Submerged in seawater, trees that dot the now barren rice fields and its embankments have dried and wilted, leafless and lifeless.

There was a time when farmers in Bambang could wait for the seawater to drain and dry off on hot days or be washed off by rain showers, leaving the soil healthy enough to plant rice. But the risk of putting in money only to be wasted when the seawater creeps back had discouraged Buhay and her fellow farmers from planting.

“Inuutang lang namin yung pera na gamit namin doon, tapos matutunaw lang din ng tubig alat. Sa halip na makaahon kami, lulubog po kami,” Buhay said.

(We take a debt for the money we use to plant rice and then we lose it to the sea water. We’ll only keep drowning in debt.)

Buhay used to harvest up to 60 cavans of rice per season from the field beside her house where she is a “kabesilya,” the person who invites and leads a group of farmers to plant crops for a fee.

Now, she joins fellow farmers leaving Bambang to plant rice as hired help in the fields of Balagtas, about an hour away on an old motorcycle and sidecar she pieced from junk.

“Dapat doon lang kami sa Bambang, nakita nyo sa Bambang napakaluwang ng sinasaka ng mga magsasaka, dapat di na namin kailangan magpunta sa ibang lugar gaya dito sa [Barangay] Dalig,” Buhay said.

(We should be able to make a living in Bambang, our fields there would have been enough for us. But now we have to go all the way here in Barangay Dalig.)

Whenever she has time in the morning before leaving, or energy when she gets home at night from the fields, and in between days when there are no calls for hired farmers to tend to faraway fields, Buhay sorts through garbage to earn additional income.

Sometimes, she takes scraps of bread and old stocks of loaves from a nearby bread factory to resell as poultry feed.

“Malakas ang loob ko na ako hindi naman magutom kasi hindi ako nahihiyang mamulot ng kahit anong bagay. Basta at least malinis ako, hindi s'ya galing sa masama, proud ako sa sarili ko,” Buhay said.

But she admits life now in Bambang has changed, and not for the better, “Sa halip na may oras kami sa pamilya namin, kasi pagdating namin gabi na eh. Kung doon lang kami nagtatanim, maaga pa kami makakauwi, magagawa pa namin ang bagay na dapat gawin namin.”

(I’m confident my family and I won’t get hungry because I don't get ashamed from picking up whatever junk. At least, I am clean, it's not from anything, I am proud of myself. But my time with my family is lost. We arrive home from the fields late at night. If we could only plant again at home, we’d have more time for ourselves.)

As Buhay and her fellow farmers move further inland to keep making a living, she shared seawater has seemingly followed them, “killing” previously arable lands.

“Hindi lang sa amin, pati sa [Barangays] Matimbo at sa Bangkal [sa Malolos]. Nagtatanim din po kami pero hindi na rin, di na rin kayang taniman,” she said.

(It's also happening in Barangay Matimbo and Bangkal. We used to plant there too, but we no longer can.)

Buhay and her fellow farmers are only the latest to join the exodus from sinking coastal areas and flatlands. For now, they have relocated where they make a living, but Buhay said she and her family are preparing should they need to uproot their lives.

“Hinahanda na lang namin ang sarili namin, sa ayaw at sa gusto namin, dahil ganun ang nangyari ano pa ba ang ikabubuhay namin?” Buhay said, as the scorching heat of the sun bore down on her capped head, looking to the horizon where her fellow farmers tilled the field.

(We’re preparing ourselves for whatever might happen. Whether we like it or not, we might have to leave home. But how will we begin life again?)

Siringan predicts land subsidence and rising sea level would drive more people away from their homes.

“‘Yung lugar na ang isang palayan pinapasok na ng tubig-dagat, hindi ‘yan bago. Marami, halimbawa sa kalupaan ng Pampanga, ganyan ang kwento, at ang mga pagbabago na ito, nangyari na noong 70’s, 80’s,” Siringan said.

“Lumulubog na sila ngayon, ikaw mismo, nakita mo na. ‘Pag high tide, walang ulan, pinapasok na siya ng dagat. Nangyayari na siya, you don’t have to project into the future, because it’s taking place now,” he added.

(This has already happened before. There are rice fields that have been lost to sea as early as the 70’s and 80’s. They’re already sinking, you saw it yourself. You don’t need to project into the future because it’s taking place now.)

While staying in these sinking communities may still be an option, the lifestyle change and necessary investment to keep even a semblance of a normal life is costly, something already experienced by locals nearer the sea like Nakaya and residents in Barangay Taliptip.

“Una kailangan nila itaas ang kanilang bahay. ‘Yung transportation nila, kung mataas ang tubig, hindi sila pwede maglakad, walang public transport, kailangan na magbangka,” Siringan explained. “‘Yung pagkutkot ng tubig-alat o alon sa lupa, mababawasan at mababawasan siya, kaya ‘yung mga struktura ay pwedeng mag-collapse, kung ang structure mo nababad sa tubig ito rin ay hihina.”

(They’ll have to elevate their homes. They’ll have to get boats to be able to move around when the water is too high. Saltwater and the movement of the sea will eat the soil away and corrode structures.)

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources is identifying areas that should no longer be used as residential, a list which can be expected “in the very near future,” BENRO's Degala said. This will allow the Bulacan government to estimate how many families would need to move, the first step of relocation.

“Alam natin, at bukambibig ng maraming government officials that sea level is rising and yet walang nafo-formulate na guidelines on coastal development. Kung ako alam ko na na tumataas ang dagat, lumulubog ang lupa, bakit pa ako mag-iinvest sa lugar na ‘yon?” Siringan asked.

(Government officials often talk about sea level rise but we have yet to formulate guidelines on coastal development. If we already know that the sea is rising and the land is sinking, why would we invest on creating structures in areas affected by it?)

PH needs to adapt to climate change, pursue mitigation

Groups call for more action from developed countries to mitigate effects of climate change

“Dapat bahagi na ng pagpaplano nila kung saan pahihintulutan na magkaroon ng housing, i-consider na nila na tumataas ang dagat at magiging problema ang coastal flooding at coastal erosion, magiging problema ang pag-alat ng tubig,” Siringan said.

Bulacan is just one of the many coastal communities of the Philippines' 7,000 islands. Bulakenyos might not be the last who would have to choose between drowning or fleeing from the sea.