"Hello"

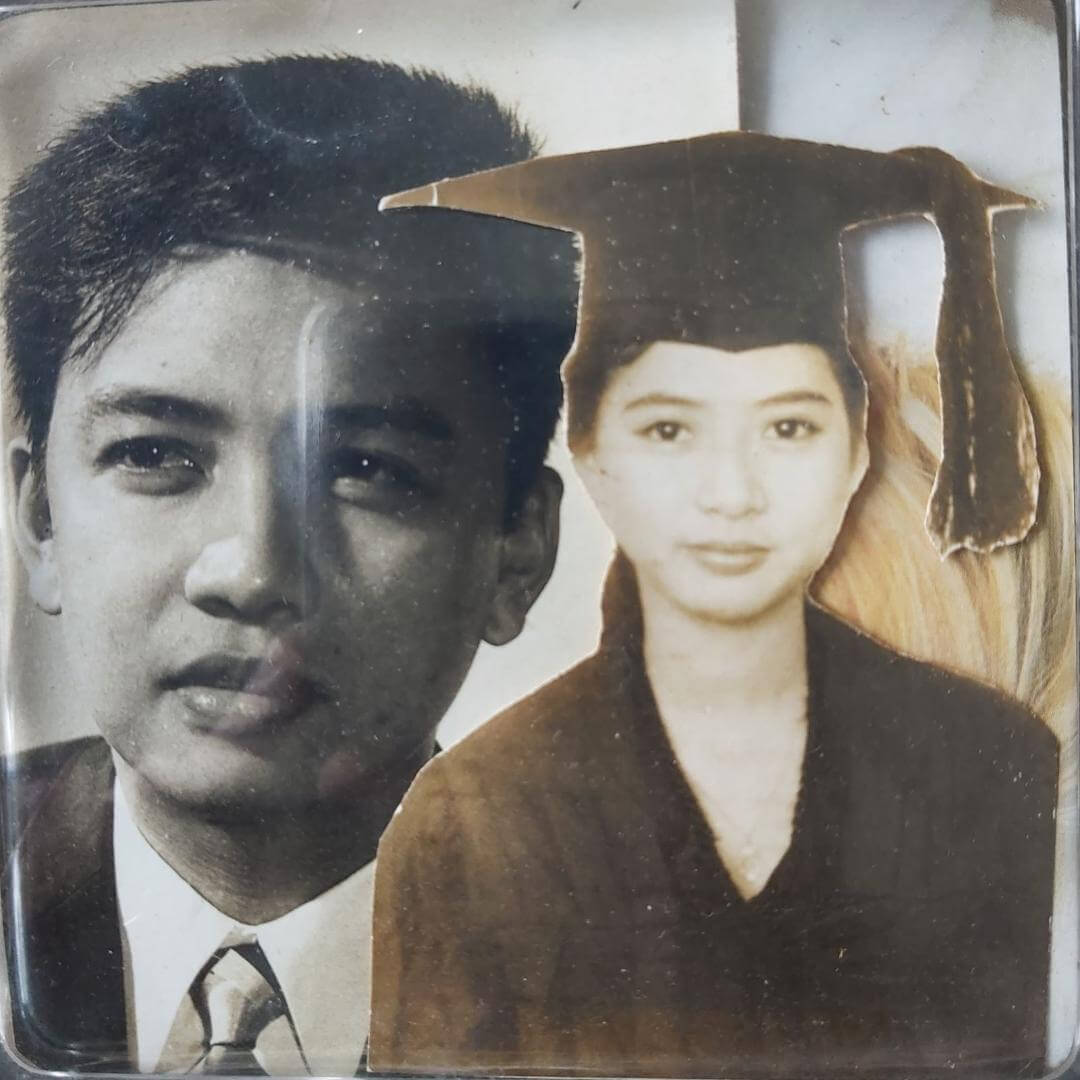

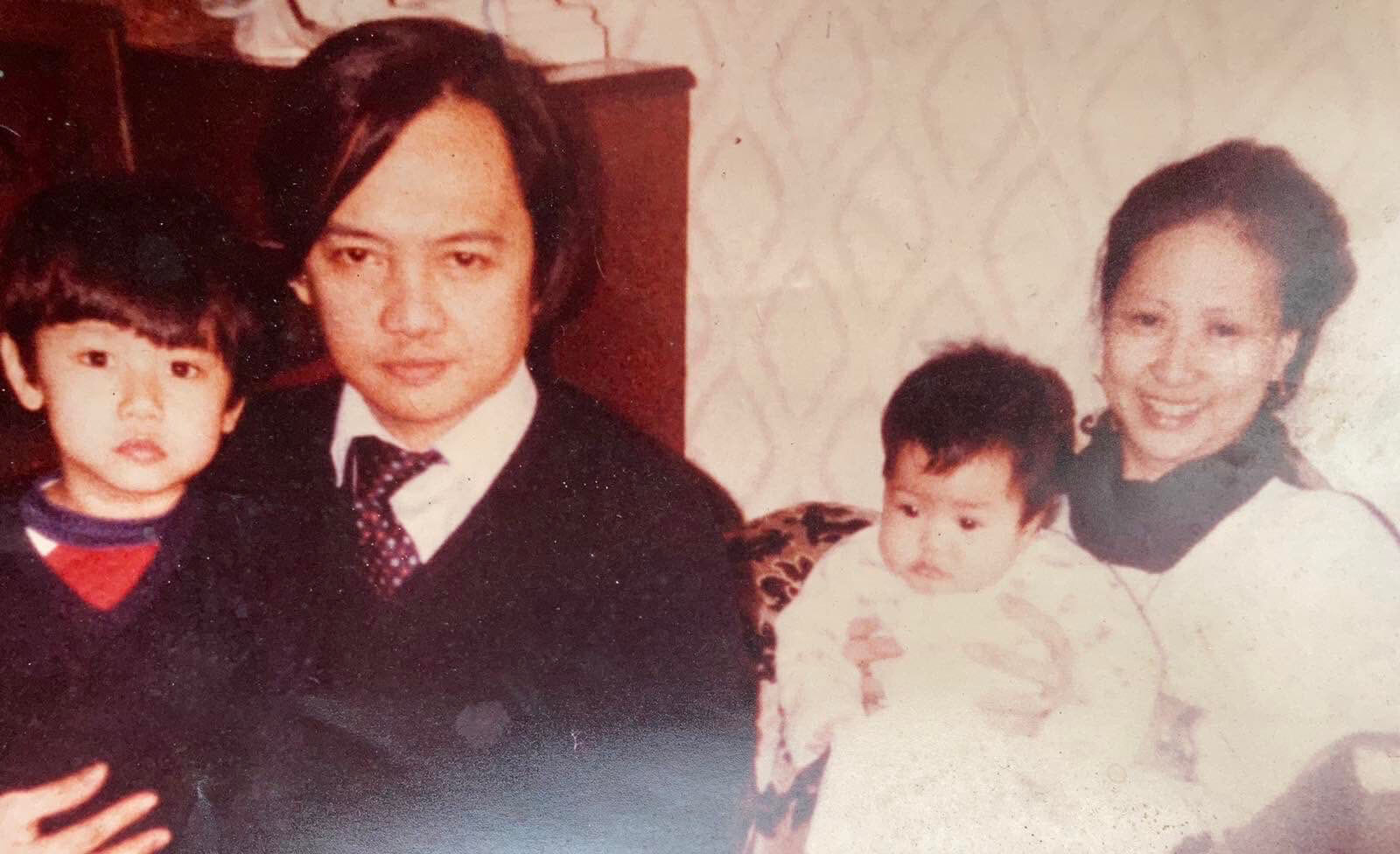

For almost 50 years, mornings felt like waking up to a dream.

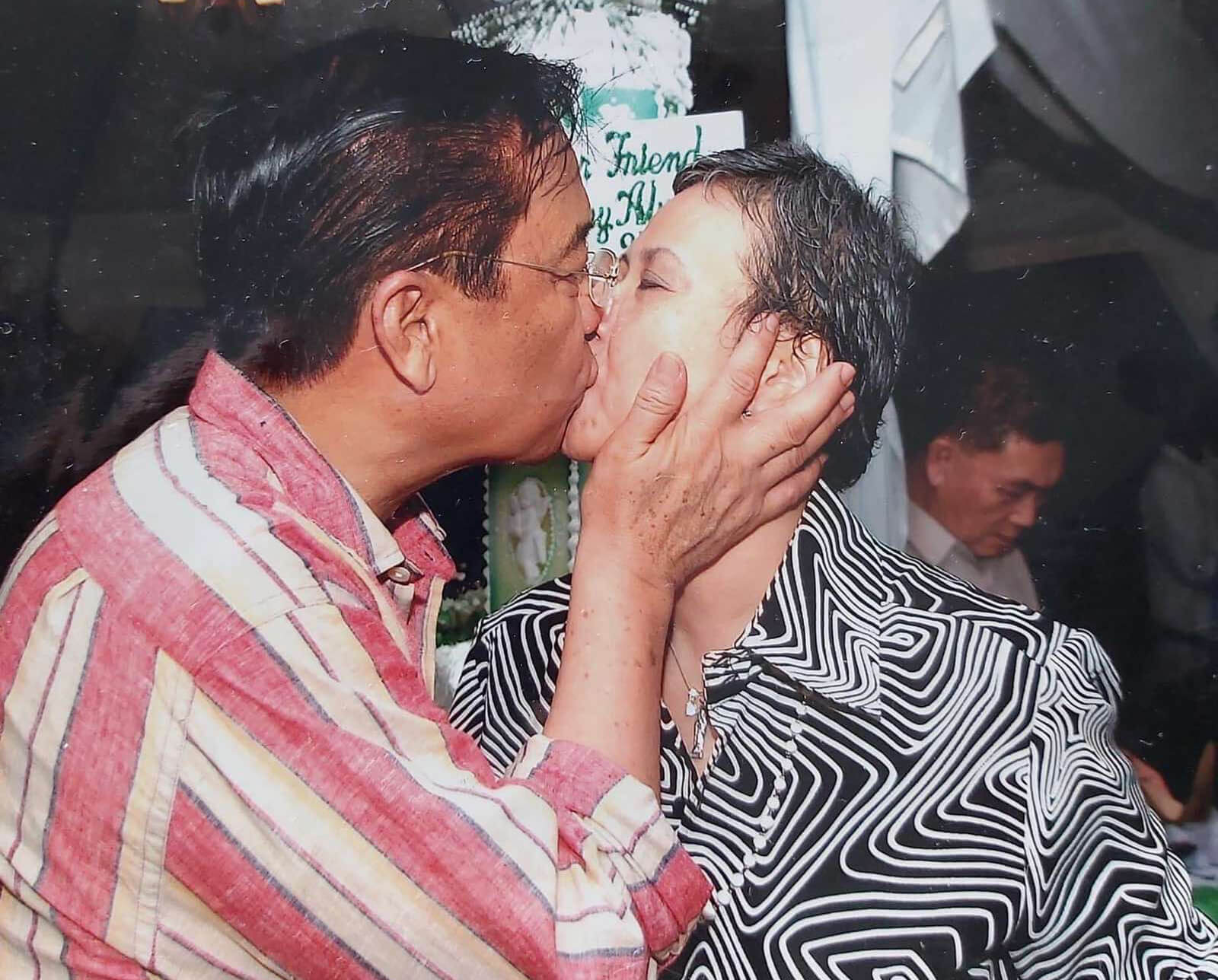

Every day, she would stir from slumber, in bed with her husband next to her. He would reach for her hand; hold it for a few seconds, in a soft, subtle grip. Fingers intertwining momentarily before parting as he raises his head to give her a peck on the cheek.

“Hello,” he would then whisper into her ear. His tone, deep and certain, would break silence before dawn.

“Ano, kakain na ba tayo?”

This is their mornings. Or rather, was.

These days, Cecile Guidote-Alvarez would wake up in an empty bed. She would open her eyes, gaze into the ceiling, and would wait for her husband’s hand to reach for hers.

The affection never comes. No hands, no pecks on the cheek, and no hellos.

And that realization almost, always grips her with the sudden pang of sadness and longing. She would run her fingers through his favorite shirt – a weathered, white camisa de chino – that, nowadays, she would often wear to sleep.

“It’s comfortable but at the same time, I feel some— maybe it’s just my mind but I feel some closeness or connectivity. I feel there’s a sense of linkage. It may sound crazy but it does help me,” Cecile says.

She knows those mornings are now truly nothing but a dream, yet she still can’t help but wait.

“Hanggang ngayon, parang may balaraw sa puso ko. Napakasakit.”

It’s an admission that resonates more coming from someone who has lived through great pains.

Those mornings are done. Her husband is gone.

Cecile has taken on many roles in her prolific career: actress, artist, author, advocate, founder of the Philippine Educational Theatre Association, executive director of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and youngest Filipina to receive the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay award.

She is known most of all as a survivor – fighting for democracy during the turbulent Marcos regime and then later on, beating an illness just as dangerous: cancer.

Now, at 77, she takes on an unfamiliar role that many women throughout the world suddenly found themselves in because of the new coronavirus: that of a widow.

It was March last year when Cecile felt the stirring of sickness. But this wasn’t like before. Her cancer had not recurred because just a month prior, doctors sent her home with a clean bill of health after another scare.

Yet Cecile felt weak, feverish and her body was stunned by malaise. Her throat hurt. She couldn’t stop coughing. Her lungs felt like they were imploding and exploding at the same time. She thought it was just a nasty case of a run-of-the-mill flu.

Her husband, former Senator Heherson “Sonny” Alvarez, took her to the emergency room at the nearby medical center.

“And we still have a wedding to go to.”

At the time, the world was just on the verge of an unprecedented lockdown because of the pandemic brought on by a new virus. The term COVID-19, now very much part of the daily lexicon, was still merely a warning in the fringes. It had not yet become the world’s axis point. So it was a seemingly distant threat and the farthest from their minds.

Their plan was simple: get a check up, a doctor’s opinion, and then go home.

But after seeing the symptoms, doctors admitted Cecile to the hospital. To their surprise, Sonny was asked to stay too for “additional tests”.

He wasn’t feeling sick or anything. At 80, he felt mostly fine, save for a sore joint or two. But with Cecile showing clear signs of infection from the new virus, the doctors wanted to make sure that he wasn’t affected by it as well.

At some point, during the shuffling of beds into the isolation wing of the hospital, Cecile lost consciousness from the severe symptoms of what would turn out to be COVID-19.

She didn’t know then. But there, in that emergency room, under the pale, frigid, fluorescent lights, was the last time she would see her husband alive.

Those mornings are done. Her husband is gone.

“Natuwa ako na sasama siya. Akala ko magsasama kami sa isang room. Sabi ng doktor, maiwan na rin si Senator. So naghihintay kami sa emergency room. Hindi ko naman alam na mayroon ‘nang kuwarto. Hiwalay pala kami.”