On Board the

BRP Sierra Madre

The grounded Philppine navy ship on Ayungin Shoal

The Philippine Marines stood on deck, feet planted on portions of the floor of the BRP Sierra Madre that were not corroded, eyes glued to the three white figures dancing at sea. The sun was blinding. But what was happening in front of them was too important to ignore.

"'Pag makalusot 'yan, bulilyaso kayong dalawang kapitan dyan (if that passes through, those two captains will be in trouble)," said one of them under his breath. He was referring to a small Philippine vessel that was trying to outmaneuver two China Coast Guard ships. The Marines knew a chase was about to happen. China Coast Guard ships had been fixtures in the West Philippine Sea for months now, patrolling the waters. To the minds of the Chinese, they owned it.

When the nine Marines watching from the BRP Sierra Madre saw the Chinese vessels make a sharp change in course, they knew what the target was.

It was like watching a horse race, made worse by the fact that they were all betting on the smallest, slowest beast that was trying to make its way into Ayungin Shoal. The China Coast Guard vessel 1127 closed in on Philippine vessel AM700 from behind. The Marines squinted as the second Chinese ship - Coast Guard vessel 3401 – arrived to position itself in front of the AM700.

Then 3401 blocked the Philippine vessel’s path, and the dance became all too familiar. They had seen this happen before – on March 9, to be exact, when a previous mission sent to extricate them from Ayungin was blocked and driven out of the shoal by similar Chinese vessels.

“Malabo na naman yata tayong masundo ah (the chances that we will be picked up from here look dim),” said Marine Sergeant Edwin Galvan, the ship’s medic.

Vessel 3401 moved in even closer, and blocked the AM700’s path a second time. Galvan and the other Marines could sense the urgency in the China Coast Guard’s movement. They waited for the water cannons to hose the Philippine ship down and drive it away, just like they saw them do to Philippine fishing vessels just the day before.

But the water cannons stayed idle, even as the AM 700 penetrated the second blockade.

"Pasok na 'yan, sabi ko, nung nakarating na ng bahura (the ship has made it through once it reaches the reef)," said Galvan. "Wala na, hindi na makakasunod 'yung China Coast Guard na 'yan, maaasar na lang 'yan (the Chinese Coast Guard won't be able to follow the ship anymore)."

The Chinese Coast Guard vessels pulled back, and the Philippine ship was finally able to enter the shallow waters of Ayungin.

"Hila! Hila! (Pull! Pull!)," called a voice from below. It was the crew of the AM700, close enough to toss their ropes aboard the old marooned ship.

Like children rushing to meet their parents at the door, the Marines ran to the BRP Sierra Madre’s portside, cheering and applauding the AM700, the white of their teeth shimmering through their unshaven faces. After five months of isolation, they were finally going home.

As the Marines whooped and waved at the visitors, the platoon leader stood quietly at the top of the ladder, helping people aboard. He introduced himself with a stern voice, but the lieutenant's emotions soon betrayed him. "I am 1st Lieutenant Mike C. Pelotera, 0-143219 Philippine Navy Marines. Assigned Marine Battalion Landing Team 12. At sa ngayon," he paused, sighed, then chuckled, "… nagpapasalamat kaming dumating kayo (and right now, we are so grateful that you have arrived)."

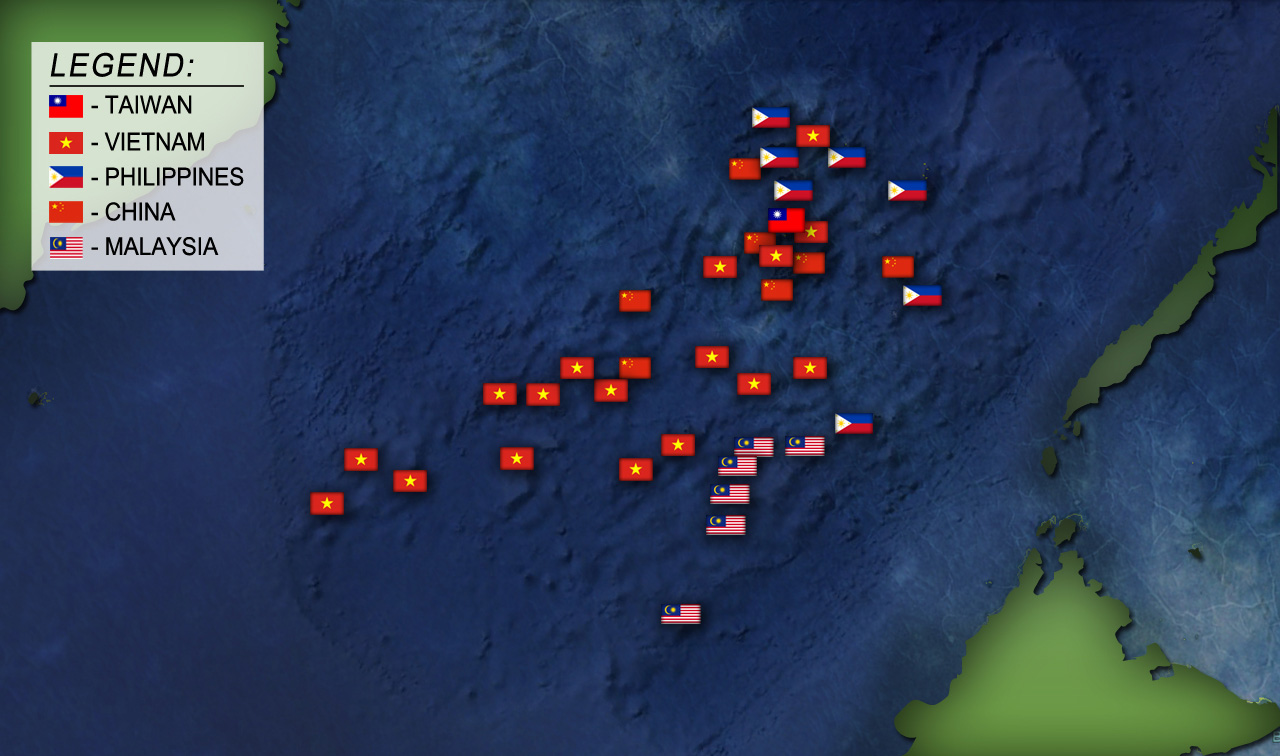

Second Thomas Shoal, or Ayungin as referred to by the Philippines, is within the disputed Spratly Islands. Six nations – the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan, and China – all claim various portions of the Spratlys. Many of these claims are overlapping.

The Spratlys have been coveted for the rich oil and natural gas deposits they are believed to contain. The Philippines claims nine sections of the Spratlys: Ayungin Shoal, Rizal Reef, Kota Island, Lawak Island, Likas Island, Panata Shoal, Parola Island, Patag Shoal, and the civilian-populated Pagasa Island. These nine sections are found within 200 nautical miles off Palawan. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea or UNCLOS, all areas situated within these 200 nautical miles belong to that country’s exclusive economic zone.

It was not lost on the group at sea that the resupply mission to Ayungin Shoal came on the eve of the Philippines’ submission of the memorial to the arbitral tribunal. The date alone made it apparent how the voyage was more than a mere resupply and troop rotation. It was a trip that sought to encapsulate all that the memorial was to contain: Chinese aggression; Philippine determination; Caught on camera.

But out on Ayungin Shoal that day, the celebration had very little to do with the geopolitics of it all. People on the AM700 cheered because they made it past the Chinese blockade without damage or injury. The soldiers on the BRP Sierra Madre cheered, quite simply, because they knew they would be with their families soon.

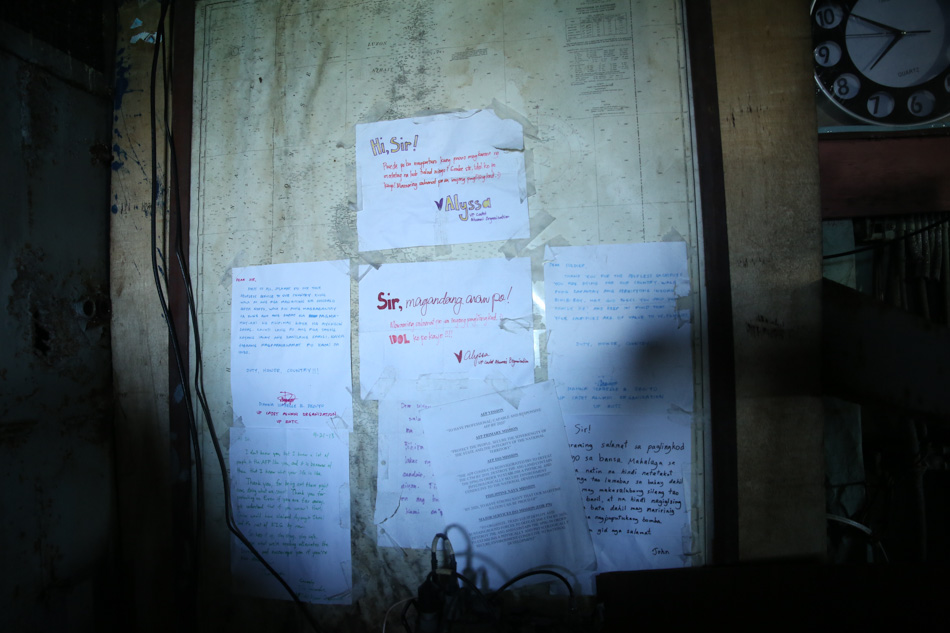

Sailors cheered when the AM700 raised its own Philippine flag, and cheered again when they hauled the first sack of supplies onto the BRP Sierra Madre. Crewmen and journalists brought out felt pens and wrote their names on the old ship. One navy woman ran to the starboard side of the old ship, and with a triumphant shout, jumped into the clear waters below. Others planted a kiss, and ran their hands across the Sierra Madre’s cold, hard hull.

In the middle of the celebration, a low-flying airplane approached. It was a P-8 Poseidon, owned by the United States Navy, and one of several US aircraft the Filipino contingent had observed throughout the voyage. The Poseidon is a combat and surveillance aircraft, capable of covert intelligence gathering at altitudes as high as forty thousand feet. But that day, it flew low enough for the naked eye to see. The large aircraft zipped past the Chinese coast guard, over the AM700, and over the Philippine flag on the BRP Sierra Madre.

No one would confirm exactly why they were there, and who exactly they were showing themselves to. But one Filipino called out and said, “Hi, uncle!” And the others laughed. By whatever measure, the Philippine contingent recognized that American presence prevented further hostilities from happening that day.

At any given point, each one of the nine Marines on the BRP Sierra Madre would say these words to reporters who would ask about life aboard the decrepit hulk of rust. They proudly gave their visitors a walking tour of the ship, albeit a slow-moving one, as the newcomers gingerly skipped over holes and tiptoed on the brittle steel of the deck.

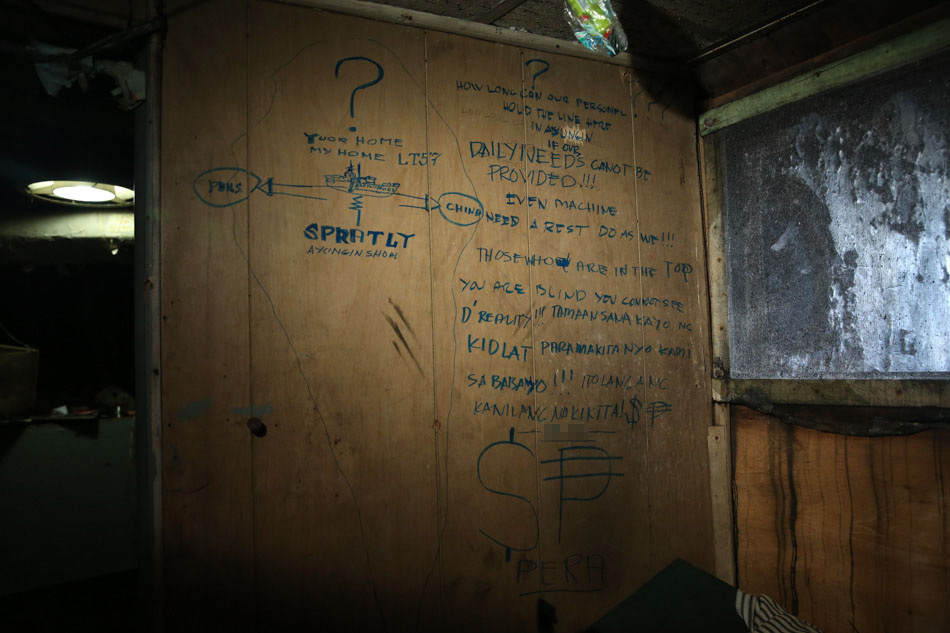

There was nothing on the BRP Sierra Madre that had not been eaten by the salt in the air and the sun overhead. Every inch of it crumbled to the touch. Gaping holes riddled its 100-meter length. Its original gray paint surrendered to the orange shades of corrosion. Its boom seemed ready to topple over.

The inside of the ship was in no better shape. Portable generators powered only the rooms inhabited by the nine Marines – the rest of the ship, not hit by the sun, is in permanent darkness.

There was little the Marines could do to improve their living situation, either. They set up a small altar on deck, where they read the Bible both to pray and to pass the time. A VCD with karaoke songs was on standby for especially gloomy nights. Makeshift benches were set up on the starboard side, so they could talk while watching the sunset.

“Marami hong aliwan dito (we have lots of entertainment here),” said Marine Technical Sergeant Joselito Panganiban. “Yung ibang tropa mangangawil, nangingisida, para may pampasalubong sa pamilya na daing. Ang daily routine ko, radio man. Magpapapawis ako dyan, magsi-sit-ups, magba-bike, sabay gawa na naman ng ibang pagkaka-aliwan (Some troops go fishing and make dried fish to bring as presents to their families. I have my daily routine as radio man. I sweat it out, I do sit-ups, biking, different ways to keep me busy).”

They hold VCD movie nights on deck on their small television, too. But the films have lost their appeal on the soldiers, and with good reason. “Pababalik-balik na `yung pelikula, halos nasaulo na namin (we’ve replayed those movies so often, we’ve memorized them),” Panganiban said. “Na-memorize na namin `yung mga linya. Ito, mamamatay `yung bida. Napanood ko na ito, paulit-ulit na lang (we know the lines already. This is where the hero dies. I’ve seen it so many times).”

“May gym din kami (we also have a gym),” volunteered Private First Class Ryan Esteban. He took us inside the ship, into a room with a single barbell. Above the doorway, someone had scratched the paint to spell the words “Mini Gym, Entrance: P5,000,000.”

Esteban next took us down a dark flight of crumbling steps, through a dark corridor that led to some of their sleeping quarters. There were old mattresses over old beds, with mosquito nets dangling overhead. The room was dark, save for some sunlight coming in from a hole in the wall, and the glow of a red ball hanging over their pillows.

It was a Styrofoam buoy wrapped in red Christmas lights. When the nine Marines received orders to protect Ayungin Shoal last November, one of them had foresight enough to buy the lights, and bring a little Christmas spirit into the ship.

It was April, and the Christmas ball still glowed. Perhaps the soldiers needed more cheer than they let on.

1st Lt. Pelotera said that the biggest challenge in Ayungin Shoal was making sure the spirit of his men did not disintegrate like the ship they lived in. He made sure his soldiers kept busy, and that their reflexes stayed sharp. “Bini-briefing ko yung troops ko, dapat [matatag yung] mindset niyo (I brief the troops, they have to stay mentally strong),” said Pelotera, who would mentally prepare them for the possibility of a longer stay. “Hindi lang months tayo dito. Dapat taon [ang iisipin niyo] (you have to think as if we’re staying here not just for a few months, but years).”

Throughout their stay, though, Pelotera said it was the clarity of their mission that kept the soldiers standing tall. “We are defending our position. Ayungin Shoal is our position. That is the reason why we are here. `Yan ang misyon ng Armed Forces (that is the mission of the Armed Forces), to protect the people and the sovereignty of the state.”

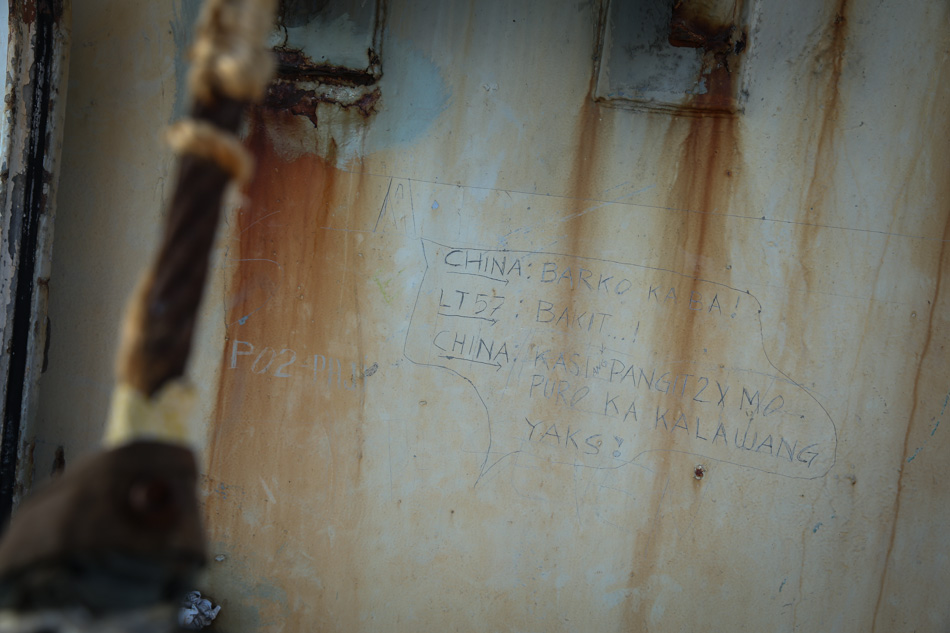

It was a message written with a felt pen, clearly at a time when the writer had no fear of an audience. The soldier is unnamed. But in the dark of the ship, his words rang in silent rage.

The visitors who walked across the length of the Sierra Madre viewed the ship with more than a hint of sorrow. This is where our soldiers live? This is our frontline of defense against the encroachment of China? Journalists took in its impressive size, and tried to imagine what it once looked like.

But among the group, one pair of eyes looked at the BRP Sierra Madre with familiarity and nostalgia only he could understand. In 1993, Navy Lieutenant Senior Grade Ferdinand Gato – the head of the Ayungin mission- rode this very ship across Philippine waters.

“Na-assign ako doon as a deck and gunnery officer. Ibig sabihin, ako yung in charge sa cargo, sa baril, at panatilihing maganda yung barko (I was assigned as deck and gunnery officer. I was in charge of cargo, guns and maintaining the ship),” said the mission head.

Before deliberately being run aground in Ayungin Shoal in 1999, the BRP Sierra Madre, also known as the LT 57 (landing ship tank) used to serve as a hospital ship for troops in battle, and transport for soldiers headed for combat. It once carried helicopters and tanks, and had fired its guns for the Philippine government more than once.

The BRP Sierra Madre was in Basilan to support troops during the secessionist movement of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) in Mindanao. In 1989, it was deployed to Mactan to restore order when Air Force Brig. Gen. Jose B. Comendador closed off Mactan to air traffic as part of the coup d’ etat attempt against then-President Corazon Aquino. In 1991, it was one of the first vessels to penetrate Ormoc right after the flashfloods that killed thousands. It also provided safe transport for ballot boxes during two elections in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao or ARMM.

It was once awarded Service Ship of the Year for at least five consecutive years. But before reaching Philippine shores, it had already served the United States during World War II and the Vietnam War.

While everyone was busy hauling supplies and taking photographs, Gato quietly made his way to his former cabin. He did not stay there long.

“Ako’y nalungkot (I’m saddened),” admitted the mission head. “Kasi napakagrabe na. Halos hindi mo na kayang tingnan sa kalumaan (the condition is so poor. You can’t even look at it because it’s so old).”

He walked out onto the deck, but the decay was the same. “Dati nakaka-jogging ka pa sa taas at sa baba. Ngayon, para kang nakikipag-patintero dahil sa kalumaan. Baka yung tinatapakan mo ay maaaring ikaka-disgrasya mo (Before you can go jogging above and below deck. Now you have to avoid stepping on dangerous areas).”

That Lt. Gato knew of the ship’s battle-tested history, and once felt its power under his own two feet, made it harder for the navy man to look at his ship’s current state. But he did not have time to reminisce.

The sun was setting. The two China Coast Guard ships that had chased the Philippine group had taken positions surrounding Ayungin – one behind the stern, the other at portside. A third China Coast Guard vessel stayed in front of the BRP Sierra Madre, between the Philippine ships and the Chinese-occupied Mischief Reef.

Gato’s mission was clearly not over yet. “Ano kaya ang susunod na gagawin nito? Ako ba’y haharangin palabas? O hahayaan na lang lumabas? Hindi matanggal `yun sa isipan ko (What will this ship do next? Will it try to block us when we leave? Or will it let us pass? I can’t shake this off my mind).”

That night, a bright beam of light shone from the Chinese ship at the back of the BRP Sierra Madre. It panned from left to right, scanning the seas for any other vessels making way into the shoal. Several times, the beam would shine on the AM700, so bright that it could illuminate the ship from kilometers away.

Ferdinand Gato chose not to sleep that night.

“Masasabi kong tapos na `yung misyon, kung ako’y naka-landing na sa mainland. Kasi anytime, kayang-kaya nila tayong tirisin, na hindi naman tayo papayag (I can only say mission accomplished once we reach the mainland. We can be crushed anytime, but I won’t allow it).”

China has said that the Philippines’ push for international arbitration has undermined the relations between the two countries. In a statement posted by the Chinese Embassy ‘s spokesperson in Manila Zhang Hua on the embassy’s website, China reiterated that it does not accept arbitration because it wants to resolve the dispute through bilateral negotiations. China explains its historic and legal basis for its claim over the Spratly Islands. It insists that the Spratly Islands do not lie within the boundary of Philippine territory as delimited by international treaties including the Treaty of Peace between the United States and Spain in 1898.

Furthermore, China insists it “has every right not to accept the arbitration initiated by the Philippines… the framework of the [UNCLOS] is not applicable to all maritime issues. First, the disputes between China and the Philippines are principally territorial disputes over islands, which are not covered by the [UNCLOS]. Second, according to the Convention, in case of disputes over territory, maritime delineation and historic title or rights, a signatory to the Convention may refuse to accept the jurisdiction of any international justice or arbitration as long as it makes a declaration."

Aside from bilateral negotiations, China favors “joint development” in the Spratly Islands which, China says, shows its sincerity and good faith. In the embassy’s statement, China claims that “the Philippine side has been playing up the issue of Ren'ai Reef [Ayungin Shoal], playing cards of sympathy everywhere, and including the issue into the so-called international arbitration, with an aim to gather sympathy and trust of the international community and legalize its occupation of the Ren'ai Reef.” China says the Philippines has been using the cover of reprovision of supplies to the grounded BRP Sierra Madre in its attempt to build facilities on the reef. -- by Paul Henson, ABS-CBNnews.com

On the day that the Philippine government filed its memorial before the arbitral tribunal, the Philippine flag was raised by a new set of Marines, symbolic of the fact that they would be the guardians of Ayungin Shoal from that day on. The national anthem reverberated across the BRP Sierra Madre, sung by soldiers and journalists alike. Some ended the song with tears in their eyes. A boodle fight of canned sardines was served, as both a sendoff to the old and welcome to the new.

1st Lt. Mike Pelotera, TSgt Joselito Panganiban, PFC Ryan Esteban, TSgt Julio Ventoza, PFC Mario Pajarillo, Cpl Rogelio Tabilisma, Sgt Rey Sarmiento, Cpl Sheffrey Luna, and Sgt Edwin Galvan then boarded the AM 700, and waved at their ship, their desolate home of five months, one last time. Back in the mainland, they will come to be known as the Ayungin 9, and awarded bronze crosses for bravery, as the defenders of the West Philippine Sea.

The Chinese Coast Guard vessels were still there as the Philippine ship pulled out of Ayungin. But none of them made a move this time. Soon, Ltsg Gato’s mission would be officially complete.

On the day the AM700 steamed home, the memorial was being submitted to the international tribunal. As news and video of the Chinese blockade spread, so too did negative reactions from the Chinese government, condemning the Philippine government’s use of the media to further their propaganda.

The memorial, and the success of the March 29 mission, would now make it more difficult for succeeding Philippine missions to Ayungin Shoal. The Filipinos seem to have won this round. But it remains to be seen who will emerge victorious in the confrontations to come.

Soundtrack on map by Valik Sparks_CC

Video of Sea Chase by Agence France-Presse