Three Young Faces

of Tragedy

ABS-CBN News

ABS-CBN News Digital

‘Yolanda’ forces young girls into prostitution

THE first time it happened, she thought they were just going to talk.

Then 16 years old, Megan had no idea that the meeting would be the beginning of her initiation into prostitution. A woman from their village had arranged that meeting with her first would-be client when she was in her third year of high school.

"Sinabihan ako na ‘sumama ka sa akin, kasi maganda dito, magkakapera ka. Malaki ‘yung kikitain mo.’ Sabi ko: ‘ayoko’,” she said.

“Tapos, after a week, nag-text na naman siya sa akin, sabi, ‘makikipagkilala ka lang,’ tapos ‘yun na, napilitan na ako, kasi ‘sinakay ako sa sasakyan tapos dinala ako sa motel, doon kami nag-usap. Nabigla ako, tapos doon na. Gusto ko na sana tumakbo, pero pinigilan niya ako," she said.

Since that day, four years ago, Megan has been a sex worker in Ormoc, Leyte. And it has been lucrative. The reason, she said, might come as a surprise to many: Typhoon Yolanda in 2013, one of the worst disasters in the Philippines that left a trail of destruction as it barreled through the Visayas and Palawan.

"Malakas po," she said of the flesh trade in Ormoc, one of the worst-hit cities.

Looking back, Megan, now 19, talked about the experience without thinking twice, recalling her descent into prostitution matter-of-factly, before and after the Yolanda devastation.

But there are moments when she stared with the eyes of a wounded animal.

Megan was in Cebu when “Yolanda” smashed into Ormoc. She hurriedly went back to Ormoc to look for her grandmother who raised her since she was a child. Her grandmother was safe, but the next days and weeks proved very difficult for them. It was a nightmare looking for ways to survive.

Megan soon found work doing the only thing she knew—trading her body for cash. She said business came along with the influx of aid workers, including foreigners, into the city.

"Marami ‘yung kumokontak,” she said. “Ang iba raw kasi mga dayo daw dito, nagpupunta sa loob, nagbibigay ng tulong, nagbibigay ng relief goods, tapos naghahanap daw ng mga...kagaya ko."

Many of those lured into prostitution were also minors, she said.

"Pagtapos po ng bagyo, mas dumami,” Megan said. “Kasi sa tingin ko walang pagkain, wala silang panggastos. Mas bata pa sa akin, meron din. Kahit na anong edad eh. 15, 16. ‘Yun kasi ang mas kinakailangan ng mga kumokontak. Hawa hawa na. Nae-engganyo yung mga magkakaibigan."

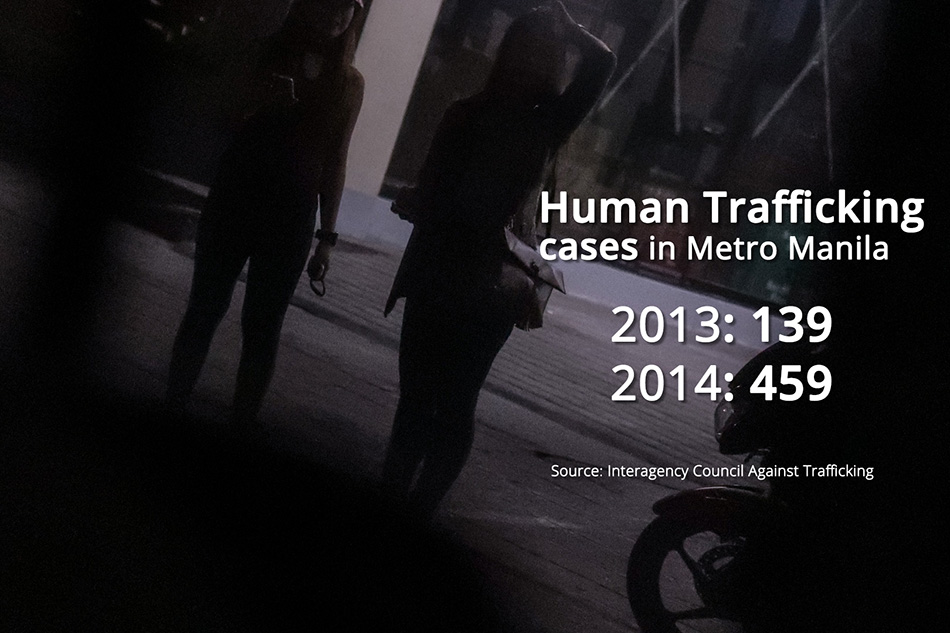

Megan said trafficking of adult and minors was on the rise in Ormoc, but a report by Interagency Council Against Trafficking (IACAT) from 2003-2015 shows otherwise.

Although there were 45 recorded cases of trafficking in Leyte in 2013, the highest in more than a decade, the trend has been decreasing since, according to IACAT.

But social workers confirmed sex trafficking increased in the months after Typhoon Yolanda.

In Ormoc, the City Social Welfare Department recorded 10 cases of child sex trafficking since 2014, with two instances involving a 13-year-old and a 15-year-old still pending in court.

"Definitely, may mga cases na hindi na nare-report,” says Gloria Malasarte, Social Welfare Officer 3 of CSWD Ormoc. “Yung iba naman ayaw na ituloy yung kaso nila sa korte. But our city government is working hard to eliminate the problem of trafficking."

Malasarte’s observation was supported by a study by the International Organization for Migration and the International Labor Organization (IOM-ILO), citing information gathered from government sources and non-government groups.

In one account, a 16-year-old girl travelling with two men was stopped at the port of Ormoc only a few days after Yolanda.

Indeed, because of the profound impact on their livelihood, most victims of trafficking have ended up in other provinces, making Eastern Visayas a source.

So said Carmela Bastes, Head of the Women and Children's Shelter in Tacloban, which houses some victims of violence, rape, and trafficking until they can be reintegrated in the community.

They've recorded 10 cases of child sex trafficking in Tacloban since 2014, with three

cases filed in court, she said.

But it was worse in other areas.

In a single incident for example, 15 women from Tacloban were rescued in a karaoke bar in Pampanga. These women had been promised jobs as domestic workers but were coerced into the sex trade instead, she said.

The IOM-ILO study revealed that many trafficking victims eventually end up in Metro Manila and Cebu. Indeed, IACAT data showed that the number of sexual trafficking cases in NCR more than tripled from 2013-2014, jumping from 139 to 459. However alarming these numbers are, it might not reflect the extent of the trafficking problem.

"Iba-iba ‘yung data, hindi nako-consolidate,” Bastes said. “’Yun din ang nakita naming problema noong nagkaroon ng national meeting. Minsan ang narereport lang, kung saan na rescue ‘yung victims, hindi na nate-trace kung saan dinadala at saan nanggaling. May gap sa data, medyo kanya-kanya pa rin ang agencies."

Kids leave schools to do hard labor

THE impact of Typhoon Yolanda on children extends beyond trafficking, which is only one form of child exploitation. Lack of opportunities and loss of livelihood means survivors have to find work wherever they can--and children share the burden of providing for their families.

Such was the case with 16-year-old Jericho, who carries a beam of wood weighing over 50 kilos through dense, swampy undergrowth in Basey, Eastern Samar.

A team of workers is clearing coconut trees from a privately-owned land to sell, and Jericho is one of several young men hired to do the heavy lifting.

Despite the heavy load and uneven terrain, he is nimble and sure-footed, crossing a flimsy bamboo bridge with ease.

For a day’s work, he would earn around anywhere between P100 and P200. Sometimes, P300 if he’s lucky.

Jericho's family had to part ways a few months after typhoon Yolanda to survive. His parents moved to another part of Eastern Samar, and he's been taking care of his two younger brothers since.

To do this, he had to quit school, finding manual labor here and there. He is now struggling to support the education of his siblings.

Jericho's stern and serious manner belies his true age.

"Kung walang bumagyo dito,” he said, “magkakasama pa rin kami ng family namin. Sa tingin ko naga-aral pa ako. Gusto kong mag-aral pero wala kasing panggastos. Tapos ‘yung makakain namin, wala naman kung hindi ako magtrabaho."

The Implementing Rules and Regulations of Republic Act 9231 or “An Act Providing for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor and Affording Stronger Protection for the Working Child” defines child labor as "any work or economic activity performed by a child that subjects him or her to any form of exploitation or is harmful to his or her health and safety, or his physical, mental, or psychosocial development."

While children below 18 years of age are permitted to work under the law, this is subject to strict conditions, including restrictions on the number of working hours, shift schedule, and the nature of work children are involved in. Hazardous work in unsafe and unhealthy environments is prohibited.

The 2011 Survey on Children conducted by ILO and the National Statistics Office placed the number of working children engaged in child labor at 2.1 million, or about 63.3 percent of the 3.3 million respondents aged 5-17 years old who worked in the week prior to the survey.

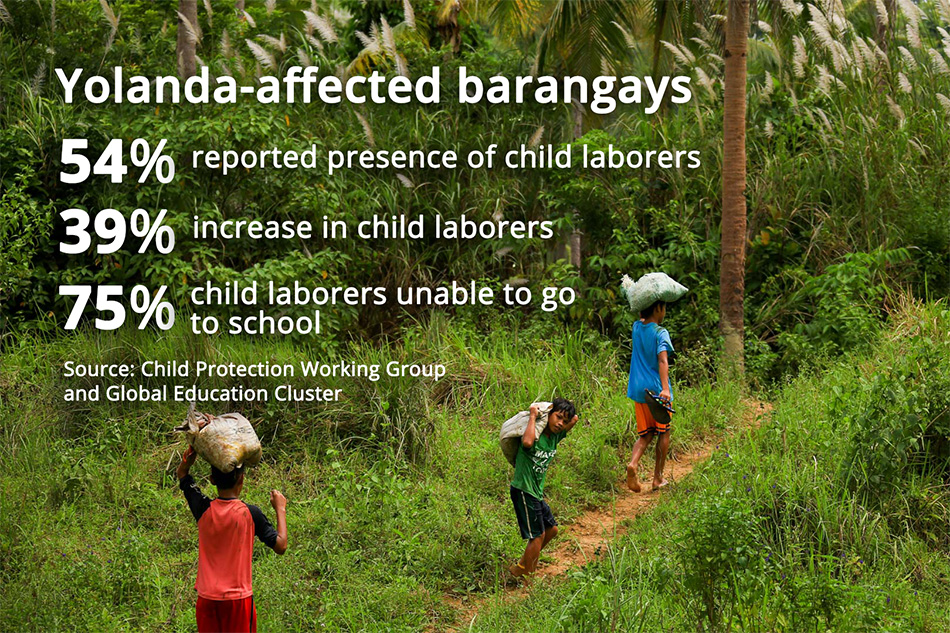

To study the impact of the Typhoon Yolanda on children, the international Child Protection Working Group and Global Education Cluster launched in February-May 2014 a joint assessment in the Philippines.

About 54 percent of surveyed barangays reported that children were involved in harsh and dangerous labor, while 39 percent of barangays reported that more children were involved in harsh and dangerous labor than before the tragedy. A staggering 75 percent of barangays reported that child laborers were not able to go to school.

Terre Des Hommes, an international development organization that promotes child welfare in Samar Island, said that child labor cases seemed to have fallen in recent months as disaster-affected communities recover.

However, the number of victims has remained a huge concern.

For example, based on their recent study, in the small village of 90 families where Jericho and his brothers lived, 17 children were engaged in labor. The youngest started working when she was just 10 years old.

Many of them worked for a nearby chicken processing plant where working conditions posed hazards to minors.

Leah, 17, once had a serious accident in the plant when her hair got caught in an automatic conveyor. She was saved in the nick of time by one of her coworkers, but the accident left her head and face severely bruised.

Leah was sent home with some pain killers. Two days later, she was back at work. The P113 she earned per day, she said, was simply too precious to nurse an injury.

"Wala na po kasing pambili ng bigas," she said.

Donabelle Abalo, TDH Samar Field Office project manager, said that it was difficult to deal with child labor in impoverished areas because children themselves looked for work to augment the income of their families, often under desperate circumstances.

In some cases, like those of Jericho and Leah, they were the family’s main breadwinner.

"Yung mga bata, sila rin ang nao-obliga,” said Abalo. “Kahit hindi sila pinupuwersa, nao-obliga sila. Sa community naman, parang accepted lang kasi ang norms na ‘yan. Parang ang pagtingin nila, ok lang, pero ang hindi alam ng ibang parents, na nade-deprive ang bata sa kanyang mga karapatan. Ang problema, kung sumusweldo na ang bata ng 100 pesos halimbawa, ayaw na niyang mag-aral kasi kumikita na siya."

The Philippines was one the early adopters of ILO Convention No. 182, or the Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, in 1999. Since then, the country has made significant gains in eliminating the worst forms of child labor, enacting laws and creating necessary mechanisms.

But according to Giovanni Soledad, ILO Project Manager of the International Programme on Elimination of Child Labor, it was in implementation that the Philippines usually fell short, especially during disasters, when long-term goals made way for short-term needs.

"Lumabas sa mga discussions a few months into the response, and even after, na medyo nagkulang nga tayo sa pagbigay ng diin sa child labor sa panahon ng emergencies," he said.

Soledad said that dealing with child labor could be more challenging than other child protection issues because of its economic dimension. Children couldn’t be made to stop working without providing an alternative.

But leaving things as they were would be more damaging to children in the long run, he said.

"Madalas na sinasabi na sa panahon ng disaster, you deal with the basic needs,” Soledad said.

“’Yung mga pangangailangan sa araw na ito, kailangang matugunan agad. Para magawa ‘yan, naisa-sakripisyo natin ‘yung long-term, but ang long-term is also important. If we keep the shortsightedness, ‘yung kinabukasan ng mga bata, mino-mortgage natin. They will probably end up in vulnerable employment, ‘yung walang kasiguraduhan yung kanilang trabaho, walang social protection, walang minimum wage, on and off, at ‘yung mga anak nila, magiging child laborer din. So ‘yung cycle of poverty,magpapatuloy."

For Jericho and his brothers, these words ring true.

Jericho said he hoped that his sacrifice would be enough to give his two brothers a chance at a better future through education.

But the cycle of poverty has chained them even before the typhoon--shackles they may not be able to break on their own.

His other sibling, 13-year-old Jonri, now skipped school to find work, like hauling gravel from a nearby creek to sell for a few pesos per sack.

"Ewan ko ba diyan sa kanya,” Jericho said, “pinapag-aral ko ‘yan eh, ayaw naman. Sana ‘yung bunso, hindi matulad sa amin."

‘Yolanda’ left some children in trauma

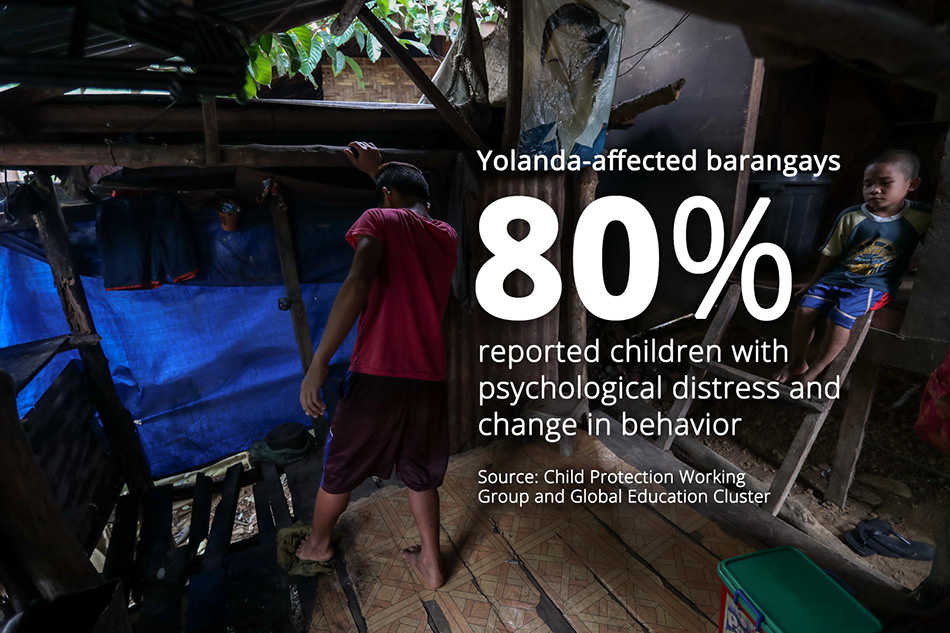

THE long-term impact of Yolanda on children also manifests in a subtler way.

Lunch break at the Tanauan School of Craftsmanship and Home Industries was a raucous event, with teenagers breaking into cliques, their chatter filling the air.

But at least one student in this junior high school did not stick around for the afternoon classes.

He was Nico Melo, 16 years old. He went straight home instead.

Nico, still in Grade 9, was already behind for his age. But while in school, he said he couldn’t concentrate, spending the days looking out the window, daydreaming.

He remembered that fateful early morning of November 8, 2013. The day “Yolanda” struck. The day he lost both parents and two siblings.

Yolanda left Nico a big scar on his left cheek. A piece of steel roofing struck his face as he was fighting for his life in the swirling water. It gave him an indelible reminder of the tragedy.

"Nagtakbuhan po kami d’un po sa may likod ng CR,” he said. “Doon kami humawak sa may puno. Paghawak sa may puno lumalaki na ang tubig. ‘Pag alon po n’un, natangay po kaming pamilya. ‘Di ko na po sila nakita uli.”

But his scars appeared to go deeper.

"Umiyak po ako n’un,” he said. “Hindi ko matanggap na wala sila. Pero hindi ko na po sila masyadong iniisip, kasi lalo lang akong umiiyak. Lalo ko lang silang naaalala."

Nico now lives with his grandmother Asela Villegas, who takes care of him and eight other grandchildren orphaned in the typhoon.

Villegas said Nico has become a problem of late, something she attributed to his age.

"Marami akong problema sa kanya,” she said.

“Nadadala ‘yan sa barkada. Minsan nga hindi ‘yan umuuwi dito. Hinahanap ko ‘yan hanggang sa may computeran. Alam niyo naman ‘yung ganyang edad. Kaya ako nabubuwisit. Sabi nga, ‘pag ayaw maraming dahilan, ‘pag gusto may paraan. Ngayon ko lang nalaman na hindi pala maganda record niya sa eskwelahan."

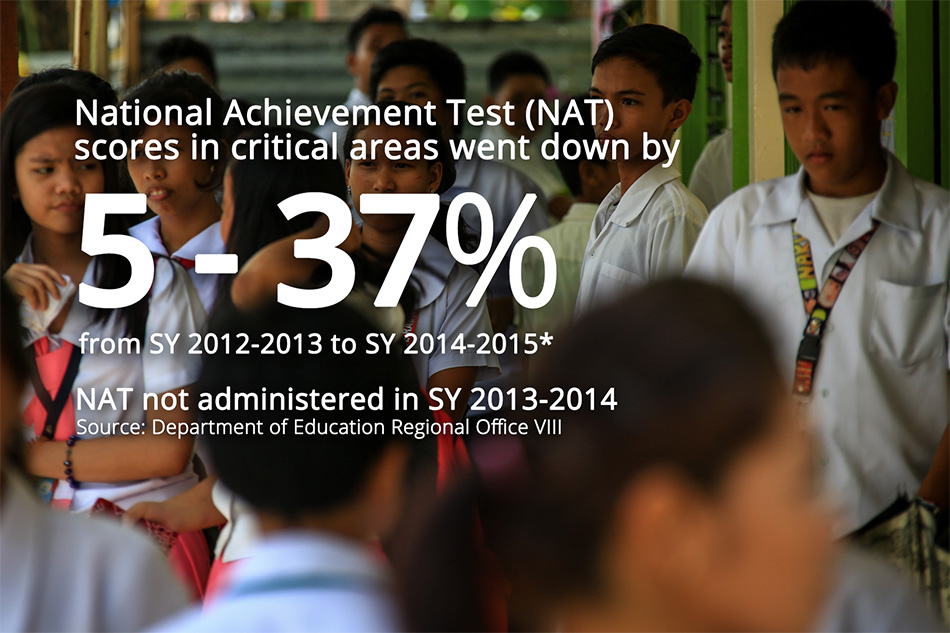

But looking at figures from the Department of Education Regional Office 8, it was clear that more students like Nico have been struggling with school in Yolanda-affected areas.

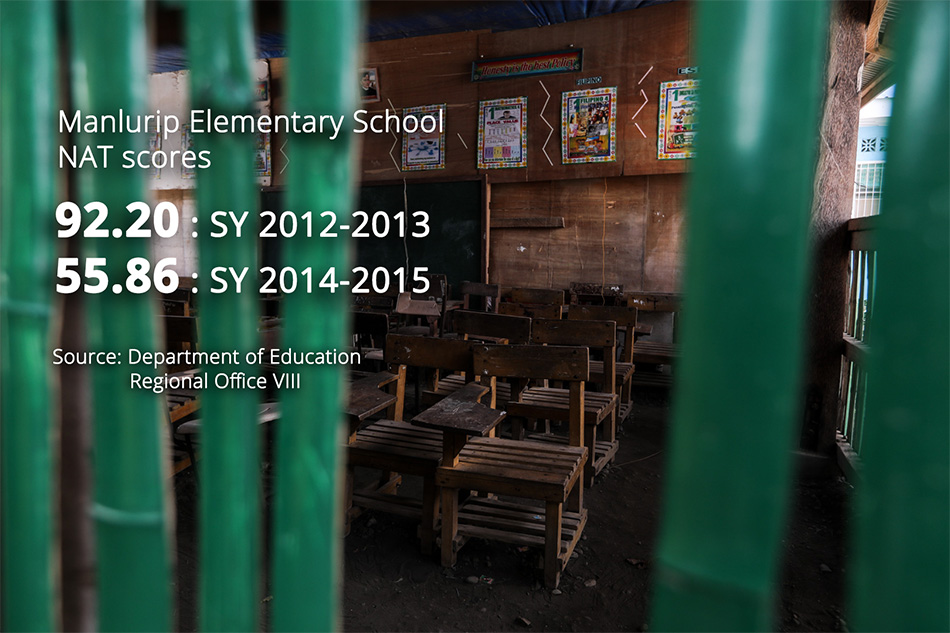

Results of the National Achievement Test scores have generally fallen between 5 percent-37 percent in School Year 2014-2015, compared to SY 2012-2013 in the most devastated cities and municipalities like Tacloban, Ormoc, Tanauan, Manlurip, Basey, Hernani, Marabut. The NAT was not administered in these schools for SY-2013-2014.

The worst dip was observed at the Manlurip Elementary School in Leyte, where NAT scores fell from 92.20 to 55.86.

To be fair, NAT scores from a few schools in these critical areas also improved.

But the figures still worry newly appointed DepEd Region 8 Director Ramyr Uytico. Using a data-driven approach, Uytico said he was empowering his superintendents across the region to design programs seeking to improve key performance indicators.

But addressing possible trauma, depression, and the psychosocial development of students was not something the DepEd could do alone.

"As a leader, siyempre we are alarmed,” Uytico said. “But we always believe in the Department of Education that it takes a village to educate a child. Kaya kung ako ang principal, talagang i-scout ko ‘yung stakeholders in the community na makakatulong sa akin to achieve the goals of the school."

Social Welfare Secretary Judy Taguiwalo agreed, saying that it would take a joint effort of different agencies, civil society, and humanitarian organizations, to address the specific needs of children.

Still, one of the lessons of typhoon Yolanda was that there should be a particular awareness and emphasis on child protection during times of crisis.

Otherwise, their plight will get lost in the chaos of the aftermath.

"Ang mga bata naman talaga ang pinaka-vulnerable kapag may disaster,” Taguiwalo said.

“During and right after the disaster strikes, all forces come into play to help in providing relief, immediate reconstruction ng physical and community areas, but the social cost, the psychosocial impact of the disaster in terms of individuals, in terms of families, kailangan mapag-aralan, at tuluy-tuloy ang efforts."

The lingering effects of typhoon Yolanda might be alarming, but there were success stories in these communities too that demonstrated the remarkable resilience of children, despite unimaginable trauma.

Maria Lee also lost both parents and sister in the typhoon. She now lives with her grandmother and studies in the same high school as Nico.

But unlike the troubled boy, the 13-year-old junior was one of the top students of her class.

Maria Lee wants to see the world, and dreams of becoming a flight attendant.

"Sobrang hirap po (mawalan ng magulang),” Maria Lee said. “Kasi nami-miss ko po ‘pag pinaghahandaan ng almusal, tsaka ‘yung may maghahatid sa ‘yo sa school. Pero ang inspiration ko rin po, pamilya. ‘Yung mga kapatid ko po at ‘yung mga tumutulong sa amin para makapag-aral kami. Ginagalingan ko po para sa kanila, para makatulong naman sa mga tumulong din sa amin."

Hopefully, it wouldn’t be too late for Megan, Jericho and his brothers, Leah, and Nico. They will need to be set on the right path and soon. With sustained and caring support from government, the private sector, and the community, their lives may not end up being defined by a super typhoon and its aftermath.